Part 2 of Srajan’s enquiry into the Seekers from the Low Lands

After Groote’s death, his follower Florens Radewijns founded a monastery in Windesheim, some 10 km south of Zwolle. From Windesheim, and from the trading cities of Zwolle and Deventer, the Modern Devotion spread across the Hanseatic world, reaching its peak in the early 16th century.

Windesheim Church near Zwolle. It stands on the site of an old monastery which was destroyed – in the 17th century – by the Geuzen, a confederacy of Calvinist Dutch nobles and their supporters, during the Eighty Years’ War against Spain. (wikimedia.org)

Windesheim Church near Zwolle. It stands on the site of an old monastery which was destroyed – in the 17th century – by the Geuzen, a confederacy of Calvinist Dutch nobles and their supporters, during the Eighty Years’ War against Spain. (wikimedia.org)

Across the IJssel river from Windesheim, near the village of Heerde, three centuries later lay the large sannyasin commune of the Stad Rajneesh, hidden in the woodlands of the Veluwe.

Across the IJssel river from Windesheim, near the village of Heerde, three centuries later lay the large sannyasin commune of the Stad Rajneesh, hidden in the woodlands of the Veluwe.

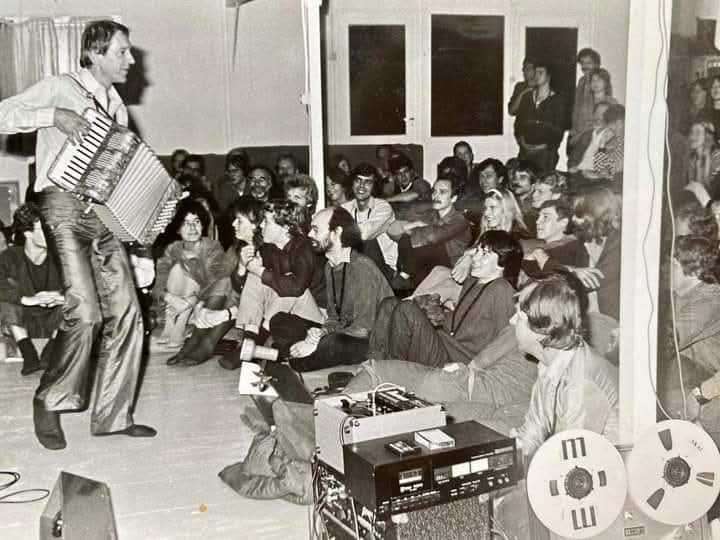

Ramses Shaffy – a beloved Dutch singer – was one of its residents, performing here at one of the many festivals and parties.

Ramses Shaffy – a beloved Dutch singer – was one of its residents, performing here at one of the many festivals and parties.

The prior of Windesheim was then the central and leading figure of a widespread monastic order, known as the Congregation of Windesheim. At its height, the order counted more than a hundred monasteries, mainly in the northern and eastern Netherlands and northern Germany. Among its famous visitors were Martin Luther and Erasmus of Rotterdam.

Born in Rotterdam in 1467, Erasmus was a Dutch humanist, Catholic theologian, philosopher, philologist and educator. He is regarded as one of the most influential thinkers of the Northern Renaissance. In his own moderate way, he sought to reform the Catholic Church from within against the backdrop of the emerging Reformation – a position that earned him enemies on both sides.

He was educated at the Latin school of Deventer, shaped by the humanist ideals of the Brethren of the Mean Life. Together with the Latin school of Zwolle, it was considered the best educational institution in the northern Netherlands. Greek had just been added to the curriculum – until then a subject reserved for universities such as Leuven or Cologne. At Deventer he also encountered Rudolf Agricola, whose example and inspiration would remain with him throughout his life.

When plague struck Deventer, Erasmus fled and continued his studies in Den Bosch – the city of the artist Hieronymus Bosch, himself influenced by the Brethren of the Mean Life.

He later entered a monastery near Gouda. There, he did not attack the ideal of monastic life itself, but rather its nitpicking rules and curbs on human freedom. Ordained a priest in 1492, he was drawn more deeply into the spiritual life, yet at the same time gained wider scope for study. In 1495 he travelled to Paris to study theology, where he clashed with scholastic theologians who, in his view, lost themselves in endless sophistry far removed from the core of Christian scripture. Here he also had the opportunity to meet the Parisian humanists.

Teaching soon brought him to England. During a six-month stay he met the young prince who would later become Henry VIII, as well as leading humanists such as John Colet and Thomas More, the author of Utopia. He also taught at the University of Oxford.

Back in Paris, he published his first book, in 1500 – a collection of proverbs titled Adagia. It became the first major success in the still-young history of printing.

In 1506, Erasmus departed for Italy where he was going to stay for three years. In Rome, the politics of the High Renaissance popes – Sixtus IV, Innocent VIII, Alexander VI, Julius II and Leo X – only confirmed the need for reform. The Borgia and Medici popes were notorious for extravagant spending, decadent feasting, hired assassins and bloody wars to expand their power base. In Machiavelli’s judgement, Julius II was a strong pope who did everything to further “the honour and the glory of the Church”.

Erasmus, however, did not mince his words about Julius II: “What is the difference between you and the leader of the Turks, except that you hide behind the name of Christ? You have the same ideas, live the same dissolute life – but you are the greatest plague upon the world.”

After Julius’ death, a biting satire circulated under Erasmus’ name, though he never admitted authorship – probably to avoid reprisals from papal loyalists. Julius Excluded from Heaven (also called Juliande) tells the story of Julius who, arriving at the gates of heaven with his guardian angel (and his army), is trying to persuade St. Peter with all kinds of means to allow him entry into Heaven. The tale lays bare Julius’ ruthless ambition and thirst for power. For Erasmus, a pacifist, such belligerence was wholly unworthy of a servant of God.

On his journey back from Italy to England, Erasmus composed his Praise of Folly. By letting a fool speak, he could mock the pompous seriousness with which people of every profession and class pursued their interests – and the grotesque short-sightedness with which they judged each other.

Erasmus later travelled to Basel, where Johannes Froben printed his two great philological works: the bilingual edition of the New Testament and his edition of the letters of St Jerome. Returning north, he was appointed counsellor to Emperor Charles V, and settled in the Low Countries (1516–1521), living in Antwerp, Bruges, Leuven and Mechelen. (These cities are now all part of Belgium, but at that time, as were the present-day Netherlands, they all belonged to the Holy Roman Empire.) His friend Jeroen van Busleyden founded the Collegium Trilingue in Leuven – a college that helped spread Erasmus’ vision of classical language studies.

He also worked tirelessly to modernise priestly training in Leuven. But his efforts and writings soon drew suspicion from conservative clergy, leading to inquisitorial persecution in the Low Countries. He fled to Basel. In France, a translator of his works was burned at the stake. His books were banned in France, and his name placed on the Index as auctor damnatus – a condemned writer.

Erasmus maintained an extensive correspondence with prominent humanists. In his final years, he lived in Freiburg im Breisgau, before returning to Basel in 1535, where he died the following year. Tradition holds that his last words were simply: “Beloved God.”

For Erasmus, God was not the stern ‘God the Father’ – the heavenly projection of an earthly autocrat, as in Jan van Eyck’s famous altarpiece.

He lived in an age of upheaval, when new ideals came to the fore. A scholar who travelled across Europe, he gained prestige in intellectual circles with his humanist critiques and pleas. Through his writings, he sought to educate, to liberate human potential, and to encourage a life rooted in both the authentic teachings of Jesus and the wisdom of the classical authors.

In the next part of this series we will speak about the mystic Jan van Ruusbroec.

Comments are closed.