Solutions for an all-year-round crop in Oregon. Notes by Saten (Part 5)

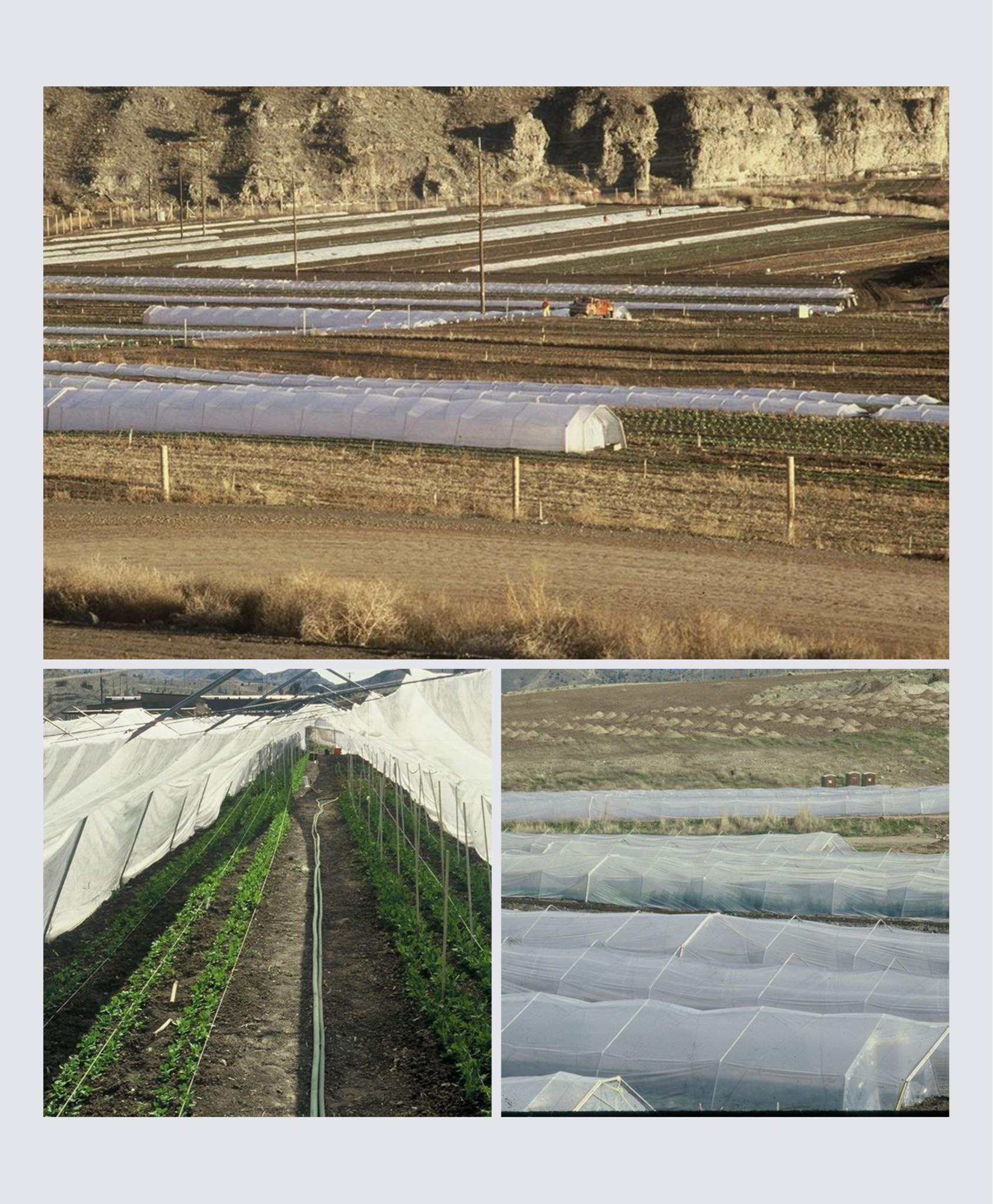

How do you extend the frost-free growing season when it is so short, and in such a severe climate – where the river freezes over in the winter and the temps go well over 100 degrees F in the summer? As you can see in the composite above, there were those walk-through plastic structures (Chilly or Cold Frames) that we put up over about 10 acres of field. They are deceptively rudimentary-looking, but with some sannyas ingenuity and many minds working together, we created a growing environment where we harvested lettuce at Christmas time and multiplied the spring and autumn productivity of the fields enormously.

The frames were made from metal water pipe that was bent to shape. The plastic actually consisted of two tubes that ran the length of the tunnels – each tube overlapped at the top by about 18 inches and was buried with soil along the other edge. We built solid ends with doors. We then inserted a small hairdryer-sized fan into each tube and the tubes inflated to provide strong insulation. We ran baling string up and over the top all the way down to keep the tube tied down to the frames.

We then put a small propane tank with a heater on it in each tunnel. Finally, we used specially-imported Israeli drip irrigation tubing, called Netafim, which was much more durable than what was on the market, and put in the beds. And then we strung micro sprinklers along the inside of the frames so that we could mist the veggies when the temps got down to low 30’s inside the frames. The water gives additional frost protection. In the morning, the first job, after the sun hit the frames full-on, was to walk down the center of each house and, just using our hands, pull part of the tubes to moderate the heating.

We purchased specialised equipment – walk-behind tractors, tillers, seeders, etc. to operate inside the frames.

We purchased specialised equipment – walk-behind tractors, tillers, seeders, etc. to operate inside the frames.

This brings up a share-a-home story – we got a lot of folks down at Surdas (as did all work places) – sometimes up to 200 or more. There was one fellow who really embraced the whole functionality of the system and took control of the operation – he was one of our stars. Something happened that caused him to get very angry and one morning we came down to the farm to see most of the plastic tubes slashed with box cutters. It was pretty sad to see.

I have been thinking about what Saddhen wrote about the irrigation dance. It brought to mind many memories and thought I would add a patchwork of memories about our irrigation systems and the very complex dance that we choreographed each morning in the daily kick-off meeting in the trailer office down next to the creek.

Saddhen mentioned in his lyrical post how it was critical to the day-to-day operation that his role fitted in seamlessly with making sure the new seedlings did not parch, the tractors – nor our friends – did not slide off the fields, the lines did not fail from too little or too much pressure, etc.

Several of us were on the tractors and, of course, although we had lots of hands in the field, it was the mechanisation from our equipment that gave us greatly-improved efficiencies. This enabled us to turn the truck farm into a model organic operation, in particular for that era. To make sure we could do our bit – plowing and cultivating and harvesting etc. – it often meant being out in the fields after everyone had gone home or before they arrived in the morning, so that we could make Saddhen’s day a little less complicated. Many of my field pics are taken from the seat of the John Deere 2440 tractor as the sun was rising or setting. We also would sometimes be out there at night working from the headlights of the tractor.

And then there was the whole drip irrigation set-up that ran through all those fields that had the plastic season-extension tunnels and walk-through frames. It is a wonderful technology that was developed largely by the Israeli kibbutzim in the desert at the time.

We used to go to trade shows to try and get the latest information and technology and connect with importers in this area as well. Most traditional farmers did not deal with it in those days because all the ancillary benefits were still being trialled by innovators (like us). Moreover, drip systems were complex systems where water pressure differentials had to be carefully managed – especially interesting on the rolling hills (so most of our drip was on the flat area). We had to learn all about designing systems that dealt with these delicately-engineered balances.

You might think of drip lines as just leaky tubes, subject to blocking from dirt. But the emitters that were pressed into these lines were another marvel in themselves! These Israeli companies, from whom we sourced lots of our drips, designed the emitters in such a way that the water had to travel through a final maze as it progressed from the main tube through the emitter and into the field. This ‘maze’ would force the water pressure up, just enough so that the emitters had a self-cleaning aspect which dramatically extended their life span in the field. The standard US option available at the time was what is still called ‘drip tape’. This is often used once and then trashed, because by the end of the season most of the emitter holes are blocked.

A side story: for many crops, the drip line did not lie on the surface for best effect, but would instead be installed a few inches under the surface and then covered with a synthetic mulch. One of our key implements in those early days was called a subsoiler. This consisted of two giant ripper teeth which you would use similarly to bulldozer’s rippers. Much of the farm had a hard pan surface in the range of about 12 to 18 inches deep – caused by years of too many cloven feet packing the lifeless soil down – which would stop the free movement of water and plant roots. This implement would fracture open that layer and make a super-dramatic improvement in fertility.

Drip irrigation had lots of other benefits. It put the water right at the roots of the plant keeping the pathways dry and navigable. It kept weeds down because they did not get watered. We could also hook up the micro sprinklers to spray a gentle mist. We used that technique in those freezing nights, near the end (or beginning) of the season, where one or two degrees would make a big difference. If you got through that night, you might get several extra weeks of abundant harvest before the bed was harvested out, or the temperatures just became consistently too cold for that specific crop.

I mentioned in Part 2, when we were talking about equipment, how clever Prasad was. He came up with a totally novel design for getting this drip tape efficiently laid. He designed a mounting frame for these huge rolls of drip tape above the subsoiler and then he welded a carefully-designed curved tube down the back of the subsoiler shank. So we would start at the beginning of the bed with the required number of reels loaded up on the frame, lower the shanks about 4 inches into the soil, put the tractor in gear and, within minutes, you would have a complete 500 ft bed laid perfectly with drip lines.

These notes were first published as Facebook posts in a closed group for Ranch Residents. They are being re-published in Osho News with Saten’s permission. Edited and curated by Navina. Photos: all shots in this article are by the author.

Related articles

- Dryland Farming in Oregon – Experiments and innovative ideas thanks to brilliant minds coming together in Dadu farming on the Ranch. Part 1 of Saten’s notes

- Boys (and girls) love machines! – In Part 2 of his notes, Saten reminisces on the faithful machines used for all farming chores

- The evolution of our greenhouses – Saten recollects the successful, and less successful, experiments in our farming practices in Oregon (Part 3)

- Planting in Surdas – Saten’s notes and photos about the planning for the following season in the truck farm (Part 4)

- Alfa-Alfa / The Enlightenment Saga – Two chapters from Arjava’s memoir, Still… Here and Now: Growing Wings in Osho’s Garden, this time from the Oregon era

Comments are closed.