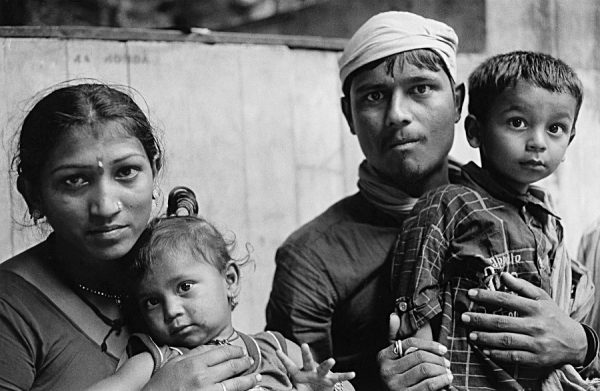

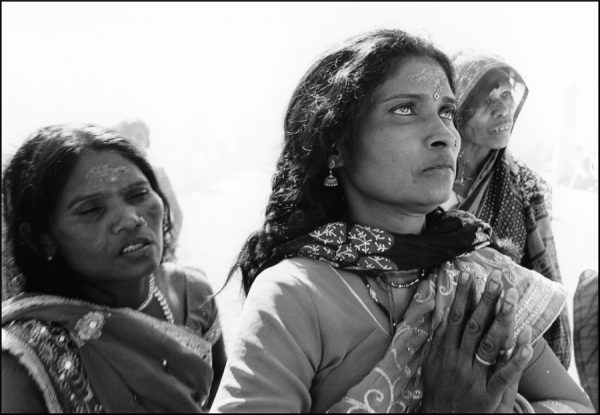

Part 1 of the photo essay, Earth, Love, Divine, by Premgit.

About 10 years ago, Sandhya and I heard of a large Shivratri celebration that happens in the Saptura range of mountains, in Madhya Pradesh. We decided to go, and struggled up the path to the top of the mountain with hundreds of pilgrims. It was a crazy scene, super crowded, loudspeakers from the small temple, lots and lots of drumming, and smoky with all the fires. Not knowing what to look for, I found it very difficult to get involved enough to photograph anything, except perhaps the press of bodies. It wasn’t until returning four years later that I began to see what it was I wanted to photograph… We went every year after that and it became a highlight of our trip.

After going to this festival, the idea of photographing the different ways of ritual worship came about. I decided to limit myself to just three pilgrimage places that I would keep returning to. One in the north, one in the centre and one in the south of India. Together these places showed me a huge diversity of peoples and culture, and I feel truly blessed that they all warmly welcomed me, allowing me to photograph what at times were extremely intimate scenes.

Mahashivratri, meaning “the great night of Shiva”, happens once a year according to the lunar calendar, falling either in February or March.

There are many legends in the Puranas about its origins, one telling of how Shiva saved the world by drinking a deadly poison which turned his throat blue: another of how he prevented the gods Brahma and Vishnu destroying each other. These days it is popular for the celebration to mark the marriage of Shiva to the mountain Goddess Parvati, but also heralds the arrival of spring and the rejuvenation of living things. Offerings of coconuts, limes, bael leaves and milk are made to Shiva for overcoming darkness and ignorance.

All Hindu gods have their own symbolic objects and these are represented in sculptures and paintings of the deity. Shiva’s most popular is the trishul, or trident. It symbolizes the balance and harmony of the three forces: Creation, Preservation, and Destruction. Most groups of pilgrims will bring at least one trishul. These are commissioned from blacksmiths especially for the festival, and can weigh up to 130 kg. Six or eight strong young men will then carry it at speed up the hill on their shoulders, chanting “Har Har Mahadev.” For self-preservation people try and clear a way, but it’s not easy on such steep narrow paths.

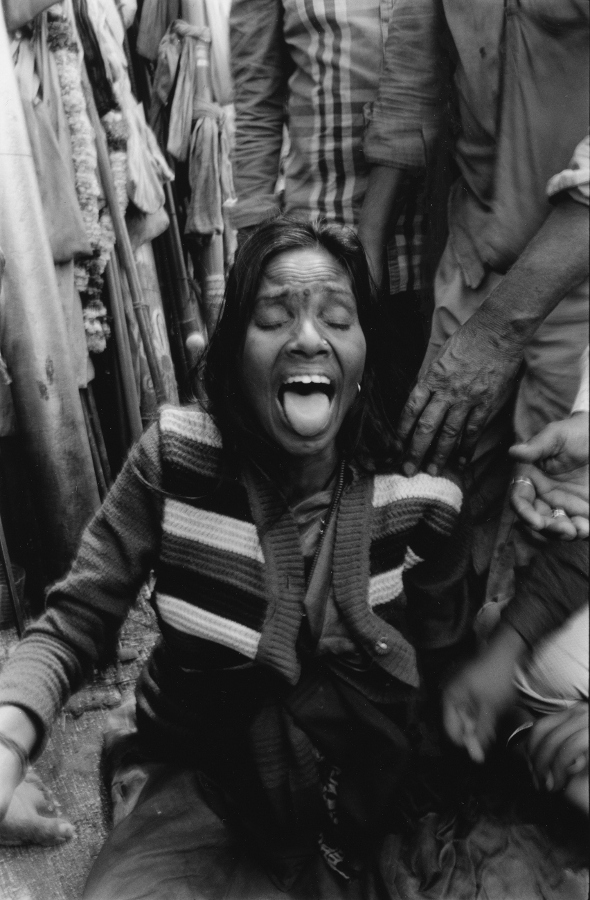

Trance States

In Adivasi culture it is common for a deceased relative to still be considered part of the community. Food is prepared and laid out as normal, although this will soon become symbolic after a short period, by putting a few drops of water and some grains of rice on the floor. This period of total inclusion lasts anywhere up to one hundred years, but generally the “second burial” takes place within a generation. During this time the spirit has to pass through two stages, the first being very chaotic and quite troublesome for the community, so to placate the spirit, they are listened to very carefully through the shaman. The second stage is one of acceptance, and the spirits’ presence is felt less and less. This stage will eventually lead to the ‘second burial’ and it is only after these rites have been performed that the person’s name is given to a newborn baby from the clan, and the circle is completed.

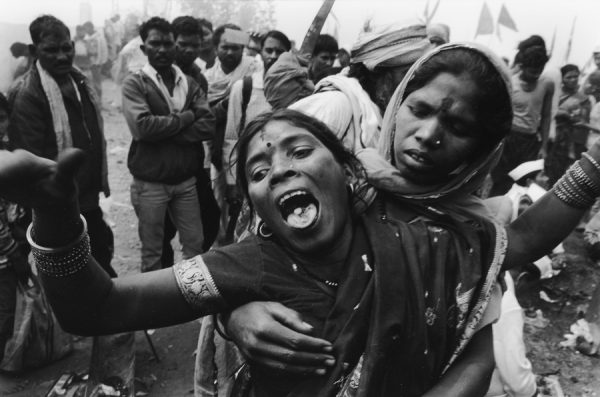

Many of the trances we have witnessed could very well be of a spirit in this first stage; a troublesome ancestor wanting to make a point or pass on some advice or information, or simply to cause a bit of trouble.

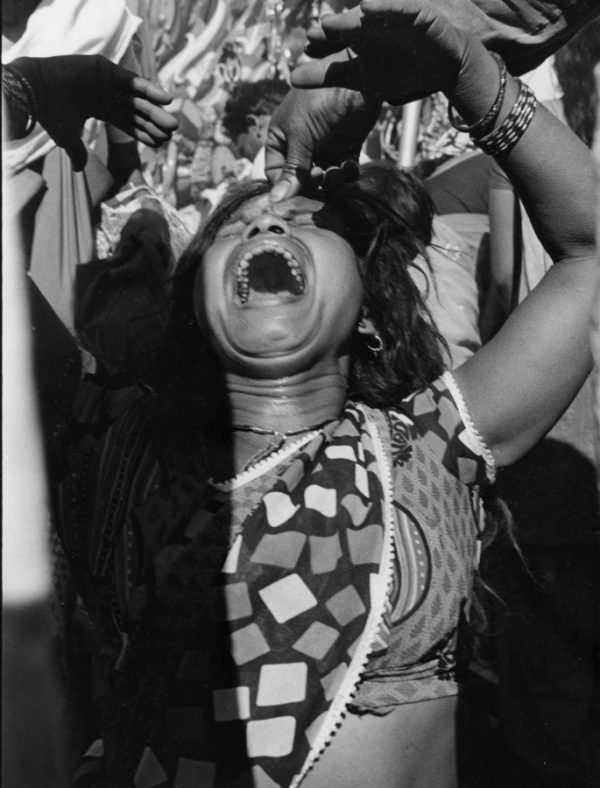

The other trances we have seen here take the form of possession by the spirit of an animal, or by a god. The snake and tiger are both popular and recognisable, and are aligned with Shiva in the Hindu tradition. They have also been revered and worshiped for thousands of years by the Adivasi communities throughout India, many still having particular animals as their totems. When the shaman is in an animal trance, there appears to be no communication with any other clan member, although he is surrounded and protected by the group, and not at all ignored.

The most recognizable divine possession is that of Kali. She is quite a fearsome goddess, and characterized by having her tongue hanging out. The shamans need no other symbols apart from their tongues to make the characterization. I’m aware that other gods are channeled in the trances, but not so identifiable.

For many of the clans and families who come to Chauragarh the shamans’ trance is a pivotal point in their time on the hill. It appears to be a totally random and spontaneous event, generally occurring after the offerings have been made around the trishuls. The attraction of capturing the fleeting trance states on film is what has kept me going back year after year.

As the shaman comes to the end of the trance, he or she is encouraged to swallow a small piece of burning camphor. This will break the trance and it is believed will safely bring them back to this plane. Very quickly afterwards the shaman will go to each clan member and bless them, often including me, then they speed off down the mountain and back to their village.

Earth, Love, Divine is a three-part photographic essay shot exclusively on black and white 35mm film using Leica M6 cameras and short focal length lenses.

To follow:

- Part 2 – Thaipussam: Celebration of Shiva’s son Muragan, Tamil Nadu, South India

- Part 3 – Ganga Puja: Which honours Mother Ganges in the timeless city of Banaras (Varanasi). Sadhus, Alleyways and Worship on the Ghats

Comments are closed.