Final part of Srajan’s series, Seekers from the Low Lands

In my early sannyas days in the eighties, after I had moved to the Chaitanya commune in Arnhem, I enjoyed visiting other communes in the Low Lands. I stayed for shorter or longer periods in several: Sharan in Haarlem, set in a stately mansion; the Stad Rajneesh in Amsterdam – first housed in a former jail, later in a monastery with many classrooms; the therapeutic centre of Grada Rajneesh in Egmond, located in a former children’s home, with a satellite in The Hague that became the precursor of Osho Wajid. I also visited centres in Nijmegen, Eindhoven, Groningen, Soest, Utrecht and Brussels, and the large commune of the Stad Rajneesh in Heerde. Everywhere, small centres and communes were springing up.

Top row: Jail in Havenstraat, Amsterdam

Second row: Heerde Commune

Third row: Humaniversity, Egmond aan Zee

I understand that Sheela ordered the smaller communes to merge into large central ones, so as to pool resources for the world commune in Rajneeshpuram. Osho is said not to have been happy with this policy of “rounding up” all his small communes. Almost all the Dutch centres moved into the Stad Rajneesh in Heerde.

At the time, I spent several weeks in a countryside commune in Friesland called Anubhava. It was a thriving group of about 30 people living in a large old farmhouse, beautifully restored. A group of sannyasin handymen provided the income, travelling across the Netherlands to insulate houses from the outside with wooden cladding – a totally new and creative ecological idea at the time. The commune also hosted therapy groups, courses and meditation retreats.

Friesland, however, had already known a commune movement some three centuries earlier – not far from where Anubhava was located.

It was a strikingly unusual phenomenon: a rural Christian community numbering in the hundreds, including men and women with talents in medicine, languages and botany. Their example inspired similar groups elsewhere in Europe and even in the New World.

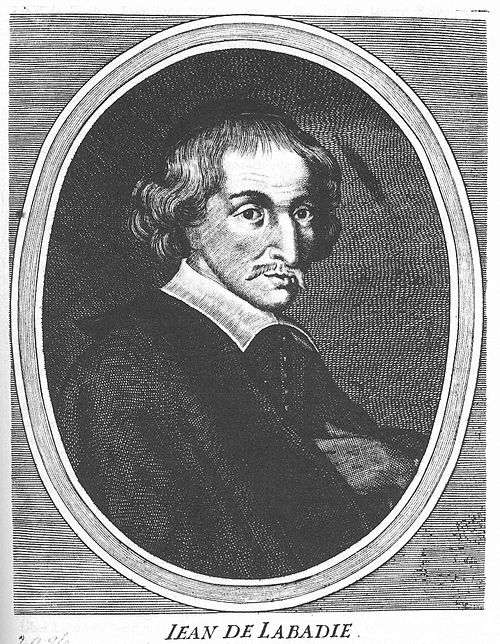

The Labadists were a 17th-century Protestant religious movement founded by Jean de Labadie (1610–1674), a French pietist. Born near Bordeaux, Labadie was first a Roman Catholic and a Jesuit. Yet the Jesuits of his day were suspicious of overt spiritual manifestations, and Labadie, who himself experienced visions and moments of inner illumination, soon grew restless. He left the order in 1639.

Labadie had contact with several religious currents and, frustrated with Roman Catholicism, in 1650, he joined the Reformed Church at Montauban and became a Calvinist. In Geneva he was hailed as “a second Calvin”, though he began to question the permanence of established Christianity itself.

In 1666 Labadie and several disciples moved to the Netherlands, joining the French-speaking Walloon congregation of Middelburg. Here he promoted active renewal through Bible study, house meetings and a life of practical discipleship – all novel in the Reformed Church of that time.

By 1669, aged 59, Labadie broke away from all churches and established a Christian community in Amsterdam. About sixty adherents lived in three adjoining houses, sharing possessions according to the rules of the early Church, as described in the New Testament Book of Acts.

Persecution soon drove them on, just after a year: first to Herford in Germany, then to Altona in Denmark, where Labadie died in 1674.

The Labadists supported themselves through crafts, while as many men as possible travelled on preaching missions to neighbouring towns. Children were educated communally; women held traditional household roles. A printing press was set up, producing Labadie’s own writings and those of his colleagues. The most famous publication was Anna van Schurman’s defence of her decision to renounce her public reputation and join the community. Known in her day as “The Star of Utrecht”, van Schurman spoke five languages, compiled an Ethiopic dictionary, played instruments, engraved glass, painted, embroidered, and wrote poetry. And at the age of 62, she left this life behind to live with the Labadists.

After Labadie’s death, his followers established themselves at Walta Castle in Wieuwerd, Friesland, owned by three sisters Van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck, who were devoted to his cause. The community thrived there, combining farming, milling and printing. Hendrik van Deventer, a physician and chemist, set up a laboratory in the castle and treated patients, including Christian V, King of Denmark. He later became known as a pioneer of Dutch obstetrics.

The Nicolas Church of Wieuwerd has a crypt where also several members of the Labadist community were buried. In 1765, during building works, it was accidentally rediscovered – four remarkably naturally-preserved mummies were found inside, dating from the early 17th century. Their clothes were still intact, and they looked as if newly laid to rest. A set of ivory dentures was also unearthed, thought by some to have belonged to Anna van Schurman, one of the few women of her time who could afford such a rarity.

A similar discovery was later made beneath the Protestant church in the small village of Almen, near Zutphen, where 18 bodies from the 18th and 19th centuries were naturally mummified by a constant flow of dry air. Here too, the clothing was remarkably well preserved.

Several Reformed pastors left their parishes to live in community at Wieuwerd. At its peak the Wieuwerd commune numbered some 600, with many sympathisers across Europe. Visitors came from England, Italy, Poland and beyond. The discipline was strict: arrogant visitors were humbled with the lowest tasks, and fastidious eaters were told to consume what was given without complaint.

The Labadists also attempted colonies overseas. In Surinam (then Dutch Guiana), they founded La Providence on the Commewijne River. But jungle diseases and pirate attacks on supply ships doomed the settlement. The naturalist and illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian lived at Wieuwerd for a time with her daughters, and in 1700 travelled to Surinam, producing her famous Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium based in part on the Labadist plantation there.

Merian was a German descendant from a Swiss family. Between 1685 and 1691, she stayed at the community in Wieuwerd with her two daughters. Merian’s husband was refused by the Labadists, but came back twice.

Meanwhile, the mother colony in Friesland sent Jasper Danckaerts and Peter Schlüter to purchase land in America. In 1683 they secured 3,750 acres at Bohemia Manor, Maryland, from Augustine Herman, a wealthy merchant impressed by their ideals. A Labadist colony soon flourished there with 100–200 members.

By the 1690s, however, decline had set in. Communal sharing was abandoned, numbers dwindled, and by 1720 the Maryland colony had disappeared. In Friesland, the community had died out by 1730.

The Labadists upheld many traditional Christian doctrines on priesthood, marriage and predestination. Yet for their time they also espoused radical beliefs, such as:

- God is known not through rigid church law but through personal prayer and mystical devotion – the heart must be warmed by divine love.

- Worldly vanities are to be renounced, and wealth shared in the brotherhood of community.

In this four-part essay we have encountered the Brethren of the Common Life, the Windesheim Congregation, the scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam, the mystic Jan van Ruusbroec, and the Labadist community – all of whom found their base in this small, flat corner of the world, from the late Middle Ages to the many Osho Communes and Meditation Centres that mushroomed towards the end of the 20th century.

This brings me to my next project: a more detailed history of the Osho Communes and Meditation Centres in the Netherlands.

Comments are closed.