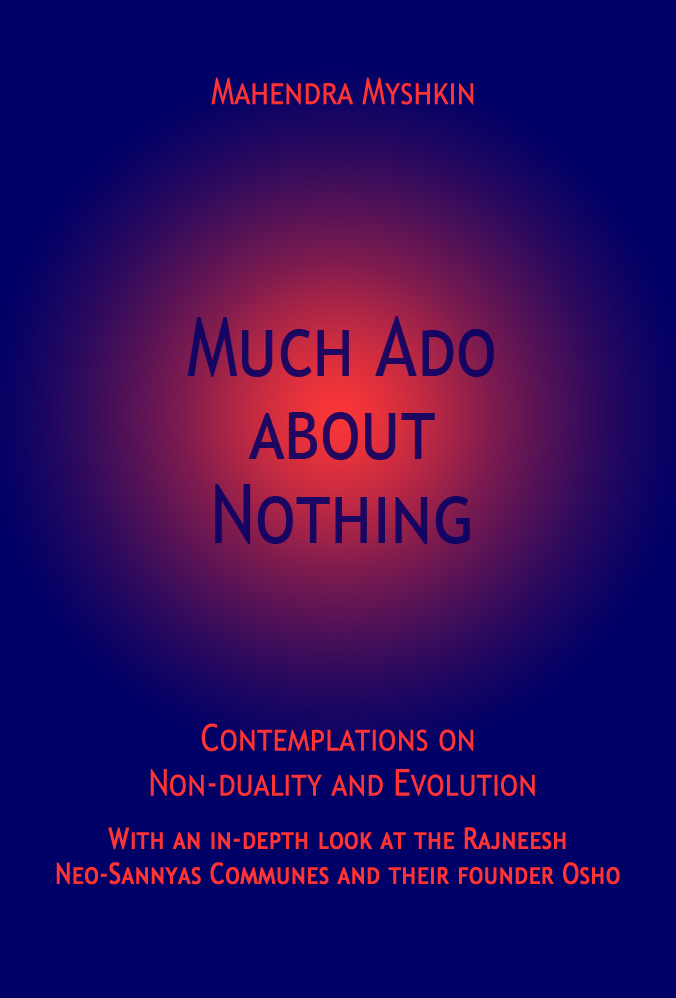

Subhuti’s review of Mahendra’s just published book, which offers astonishing insights into Osho and his work

Much Ado About Nothing

Much Ado About Nothing

Contemplations on Non-duality and Evolution

With an in-depth look at the Rajneesh Neo-Sannyas Communes and their founder Osho

by Mahendra Myshkin

ebook PDF

444 pages

Taster and links to buy on the author’s website: planetoflove.net

Or buy directly via Gumroad: mahendrix.gumroad.com

It is a stroke of genius that this book about Osho and his communes is titled Much Ado About Nothing. The author, Mahendra Myshkin, has taken his title from William Shakespeare’s famous comedy of the same name.

But whereas Shakespeare uses his “nothing” to refer to the drama of ordinary romance and relationship, Mahendra is alluding to the essential core of “nothingness” that is the centre of the universe and the underlying foundation of human consciousness.

He is referring to “Shunyata”, a Buddhist term which translates as void, or emptiness; a state of non-duality in which all distinctions between self and other, subject and object, dissolve.

This gives the reader a wonderful way of viewing the drama that unfolds as Mahendra explores the birth, growth and demise of Osho’s communes in Pune and Oregon.

Events which, when viewed through the lens of conventional morality, may seem shocking and contradictory, blend into a colourful dance of “much ado” around a “nothing” that embraces good and evil, right and wrong, and goes beyond all such dualistic notions.

But, first things first. Mahendra begins his book with the timeless and profound opening verse of Lao Tzu’s classic mystical text Tao Te Ching:

The Tao that can be spoken is not the absolute Tao,

The name that can be named is not the eternal name…

The author is cautioning the reader that any attempt to describe the ultimate truth is bound to fall short, including his own writing.

Mahendra then devotes the first section of his book to examining basic concepts of human understanding. More specifically, he highlights the flow of wisdom from East to West, which began in the 19th century, and includes the phenomena of meditation, gurus, and master-disciple relationships.

One stunning image in this section is a description of Ramana Maharshi, the great enlightened sage of South India, who, late in life, was found sitting on a rock and weeping because he longed for the solitude of the forest, instead of being surrounded and restricted by an ever-growing crowd of devotees and followers.

In sharp contrast, Mahendra cites J. Krishnamurti as an enlightened mystic who rejected his destiny as a world teacher, thrust upon him by the Theosophical Society, and then spent the rest of his life attacking gurus and spiritual organizations.

The author then uses Gurdjieff and Osho as examples of mystics who happily assumed the role of spiritual teachers, accepted disciples, and viewed the whole thing as an amusing drama, in which they were free to play tricks on their followers, deceiving them as a necessary part of their growth.

“Evil is necessary,” said Osho, in response to a questioner, who saw evil built into powerful spiritual organizations, like the Rajneesh Foundation. The mystic’s underlying implication being, “Don’t take it too seriously.”

Having set the scene, Mahendra then devotes the next section of his book to Osho and his communes in Pune and Oregon, focusing on events which seemed particularly absurd, mysterious or unexplainable.

A warning: this investigation of Osho by Mahendra is not for the squeamish. Readers hoping for an exoneration of the mystic from the so-called “wrongdoing” that happened during those times are going to be shocked and dismayed.

Mahendra was living in the communes from 1977 to 1991, so he blends his own, first-hand experience with an impressive amount of research:

“I went through a huge pile of books, I searched for as many eyewitnesses as I could find. I talked extensively with those who were in key positions. Part of my research happened in various online platforms and Facebook groups of Osho lovers and haters. Finally, I did intense research on various reoccurring themes in Osho’s talks.”

The bottom line, as far as one of the biggest controversies is concerned, is that, according to Mahendra’s research, most of the crimes committed by Sheela, his secretary in Oregon, were done with Osho’s knowledge and approval.

However, far from casting Osho as a villain, Mahendra reveals a picture in which Osho was deliberately creating an impossible situation, making decisions that would push the Oregon Ranch towards self-destruction, not as the death of his movement but as a redundant part of his ongoing work.

In this regard, Mahendra refers to Savita, Sheela’s closest aide and financial advisor, who personally informed Osho that she could no longer maintain the upkeep of the commune as well as meet his demands for more Rolls Royces and fancy jewellery.

His reply? According to Savita, the mystic simply replied, “Let the commune sink,” and Mahendra corroborates. Broken-hearted, Savita assumed that Osho no longer cared about his disciples, and left with Sheela. She could not foresee that, after being deported from the United States, Osho would spend the next two years travelling the world, looking for a place to create the next commune for his disciples.

The parallel that comes to mind, when reading Mahendra’s description of the tense and dangerous final days at the Oregon Ranch, is the Indian epic of the Mahabharata, the great war, in which Krishna, as Arjuna’s charioteer, urges the prince to fight, regardless of the slaughter that is about to happen.

Krishna’s argument is that nobody ever dies, and that those perishing on the battlefield will simply reincarnate in their next bodies, as the pilgrimage of their souls continues.

Osho’s apparent disregard for life seems similar, but with an important difference: as the drama played out in Oregon, nobody died on either side of the conflict. There was no shoot-out.

There was, however, one casualty. This was a street person, who, having been bussed onto the Ranch as part of the “Share-A-Home” program, was being bussed off again. His body was found on the snow-covered slopes of Mount Hood, halfway between the Ranch and Portland. No one seems to know what happened to him, whether it was a drug overdose, or a bad mix of medication, alcohol and hypothermia.

This review is too short to mention all the revelations and original perspectives that emerge from Mahendra’s in-depth analysis of Osho’s journey.

Significant topics include the mystic’s hidden sex life, the hoax that happened in Oregon when Osho declared 21 of his disciples as enlightened, his systematic use of hypnosis and rhetoric when speaking, and lessons he gave to Sheela on how to manipulate people, based on methods developed by Adolf Hitler’s chief propagandist, Joseph Goebbels.

In conclusion, one can say that those who feel the need to know as much as possible about what went on, in both Pune and Oregon, will not be disappointed by Mahendra’s book, but they may be deeply shocked.

Conversely, those who simply wish to focus on themselves, and on the effectiveness of Osho’s approach to meditation, may not be disturbed. They will feel that trusting their own experience is the only real test needed to assess the validity of Osho’s work, and Mahendra will agree with them.

Why? Because, as he points out, the drama of “much ado” dances around the core of “nothing”, and a direct personal experience of one’s inner “nothing” is the only thing that really matters.

Once that happens, Osho’s work is done.

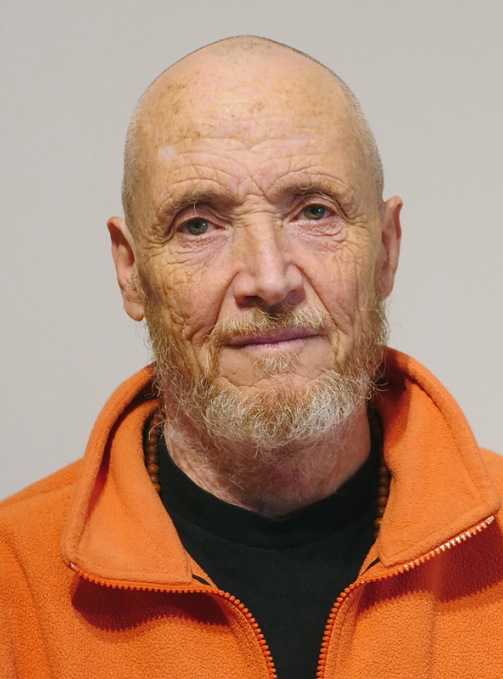

Born in Munich, Germany, in 1956, Mahendra began his spiritual journey after finishing school, traveling overland to India in 1977, where he met the mystic Osho. Over the following decades, he lived and worked in several Rajneesh Neo-Sannyas communes—including in Pune and Rajneeshpuram—before leaving the movement in the early 1990s. His later spiritual inquiries led him to study with Advaita teacher H.W.L. Poonja in Lucknow, India.

Born in Munich, Germany, in 1956, Mahendra began his spiritual journey after finishing school, traveling overland to India in 1977, where he met the mystic Osho. Over the following decades, he lived and worked in several Rajneesh Neo-Sannyas communes—including in Pune and Rajneeshpuram—before leaving the movement in the early 1990s. His later spiritual inquiries led him to study with Advaita teacher H.W.L. Poonja in Lucknow, India.

Grounding his spiritual explorations in practical life, Mahendra worked in Germany as a DJ and IT consultant. Since 2008, he has curated the website planetoflove.net, dedicated to spiritual inquiry, music, photography, filmmaking, and meditation. From 2010 to 2020, he organized public chanting and meditation events to foster shared inner experiences.

Since 2015, he has focused on writing and researching Much Ado About Nothing, integrating a lifetime of experience across spiritual traditions with critical insights into human interaction and a non-dual understanding of existence. Mahendra has contributed to Osho News with many articles.

Comments are closed.