Miraculously, Wild Wild Country, a documentary series, is what everyone around me is binge-ing on. So must you, writes Mayank Shekhar in Mid-Day, India. Published on March 27, 2018.

The sweetest personal anecdote around the late guru Osho that I’ve heard is about my friend Pooja, who was a little child, when her father Mahesh, and his friend Vinod, would pack her into the back of their Fiat, flying high on psychotropic substances, driving through the fields to the preacher man’s ashram in Pune, in the late ’70s/early ’80s.

Both Mahesh and Vinod were popular men in the movies. In the same way that Osho attracted a host of wealthy businessmen, artistes, architects, doctors, engineers, etc, from across the western world, many of whom sat across the table, decided to get their hands dirty, and literally built a whole new, self-sustained city in Oregon, called Rajneeshpuram, inside a 63,000-acre campus, producing electricity for 10,000 people, putting in place proper airport, dams, farmland, the works.

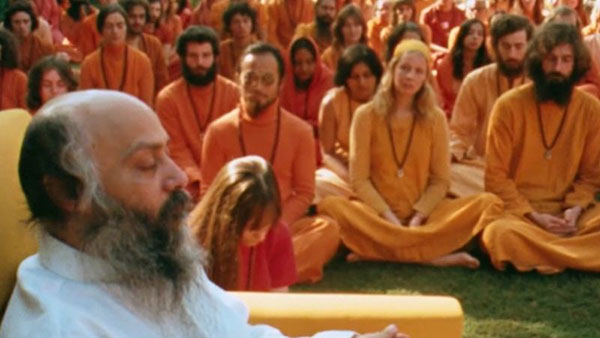

This is the subject of Maclain and Chapman Way’s astoundingly incredible, six-part (six hours’ plus) documentary series, Wild Wild Country, that everyone I know is currently binge-ing on Netflix, and is rightly struck by a story that reveals not just a godman at the height of his powers, the politics of his ashram (which is no different from the politics of the globe), but also the true nature of the United States of America that, looking at LA, Vegas, or New York City, one might assume to be the land of the free, but it remains, at its heart, very much a close-minded, conservative society, terrified of individuals who don’t fit into its White, Protestant norms.

What was it that led Bhagwan (pronounced Bagwan in Americanese) Shri Rajneesh to move out of Pune and settle in the US? A lovely law in its Constitution that allows any 150 citizens to get together, and form a new city, with its own police, and an elected municipal body, to govern itself.

How did Bhagwan manage to attract so many devotees, mainly in the US, and Western Europe? I guess this may have something to do with his teachings that aimed to merge eastern mysticism with western materialism, mixing market economy with meditation that would result, as he said, in the “new awakened man.” He embraced the riches, not just for himself (owning the largest collection of Rolls Royces in the world), but also for his corporation that was designed to create things, and produce wealth. Spirituality just comes more easily to a well-fed stomach, anyway.

As a guru, he also worked a lot like a mobile app, always unafraid to upgrade. And so he went from changing his name (Bhagwan to simply Osho), to being okay with not just getting rid of all the frills (the robe, etc) that his group came to be identified with, but even formally disbanding his whole firm that had turned into a rigid cult. He just seemed like a cool guy – whether opportunist or not is up for interpretation.

One of Rajneesh’s main draws, however, comes from the fact that he was a vehemently anti-religious god-man (an oxymoron as that may sound), offering his bhakts the freedom to pursue perceived vices – alcohol, free love, etc. Religions inevitably impose restrictions, advocate supposed virtues. What does a commune of thousands organised under such upturned principles to do its neighbours?

It freaks them out, as you see with 40 people who make up a random, sleepy retirement town called Antelope that’s quite close to where Rajneeshpuram comes up. These tight-assed blokes have obviously never been inside the relatively secretive commune. But, they’ve watched Wolfgang’s Dobrowolny’s film Ashram In Poona (1981), with disciples practising ‘dynamic meditation’ – wailing, jumping, wrestling, naked – and that’s enough for them to feel that these weirdos, walking around in their neighbourhood, dressed in red and purple uniforms, are Satanic. Red (for communism) becomes a perfect symbolism for them to adopt, and demand that the Sannyasin city be shut down.

What follows though are a series of deadly political events, manipulations, involving guns, bombs, and firepower, and a woman – Ma Sheela, the Bhagwan’s personal secretary – at the centre of what the authorities believe was the “largest wire-trapping, poisoning, immigration fraud, in the history of the United States!”

The twists and turns in this case keep you at the edge of your seat, in what’s by far the craziest Indian story, set in the US, in the ’80s, or ever. I’m simply amazed that I had no idea. What you learn from it though is what most of us have known forever: The more you attempt to change the world, the more it changes you, irreversibly!

Mayank Shekhar is an Indian film critic, journalist and author. He has been a film critic and a national cultural editor with Hindustan Times. He previously worked under Mumbai Mirror and MiD DAY. He also used to write a blog, Fad For Thought, at the Hindustan Times website. Currently, his reviews appear on his website theW14.com and also at the Dainik Bhaskar in different languages. He currently is the editorial head of Mid-Day entertainment.

Mayank Shekhar is an Indian film critic, journalist and author. He has been a film critic and a national cultural editor with Hindustan Times. He previously worked under Mumbai Mirror and MiD DAY. He also used to write a blog, Fad For Thought, at the Hindustan Times website. Currently, his reviews appear on his website theW14.com and also at the Dainik Bhaskar in different languages. He currently is the editorial head of Mid-Day entertainment.

Comments are closed.