Part 3 of Srajan’s series of essays, Seekers from the Low Lands

There were also connections to the Rhineland, where Meister Eckhart (1260–1328) sought to bridge university theology and lay piety by writing treatises in the vernacular. Though condemned by the papal court at Avignon in 1329, Eckhart laid the foundations for promoting a form of religious experience that straddled the boundary between church and world.

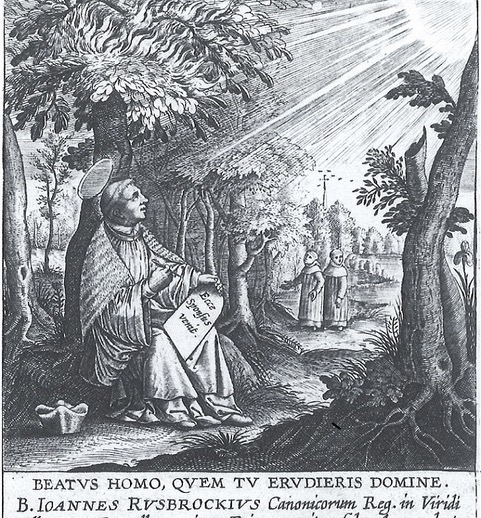

As elsewhere in Europe, fourteenth-century Brussels nurtured a mystical subculture, shared by citizens, women and clergy. Ruusbroec was likely the spiritual leader of such a circle in his early years, despite his modest status as a chaplain. His most intense mystical experiences occurred within this bustling urban society – experiences he later committed to writing.

His principal works include The Kingdom of the Divine Lovers, The Twelve Beguines, The Spiritual Espousals, A Mirror of Eternal Blessedness, The Little Book of Enlightenment, and The Sparkling Stone. Altogether, he wrote twelve books, seven epistles, two hymns and a prayer – all in Middle Dutch.

He chose to write in the Dutch vernacular – the language of ordinary people – rather than in the Latin of church liturgy and official texts, thereby reaching a far wider audience. He is said to be the most translated Dutch author after Anne Frank.

Around 1340 he produced his masterpiece The Spiritual Espousals (Die gheestelike brulocht). About 1363 he visited the Carthusians at Herne, in the Flemish Brabant, to clarify his teachings, afterwards setting down his reflections in The Little Book of Enlightenment (Boecsken der verclaringhe).

From 1349 until his death in 1381, Ruusbroec’s reputation as a man of God – a sublime contemplative and a trusted guide of souls – spread far beyond Flanders and Brabant to Holland, Germany and France.

Numerous powerful and noble figures came to visit him at the Groenendaal Priory – clerics, masters and doctors of theology among them. One such visitor was Geert Groote, who stopped to meet him on his way from Deventer to Paris. Their conversations are said to have decisively influenced Groote’s later life, and to have laid the connection between the community of Groenendaal and that of the Modern Devotion.

When Groote expressed his doubts about the orthodoxy of Ruusbroec’s writings – doubts voiced despite Groote’s great admiration – his reply was simply: “Master Geert, know this: I have never written a word unless inspired by the Holy Spirit.”

In line with the German mystics, Ruusbroec speaks of God in terms of union – of the divine and human so closely bound as to become one:

“Man, having proceeded from God, is destined to return and become one with Him again.”

Yet he is careful to qualify this:

“There where I assert that we are one in God, I must be understood in this sense – that we are one in love, not in essence and nature.”

Some of his expressions are certainly unusual, even startling.

1) the active life

2) the inward life

3) the contemplative life.

For him, at the summit, the self does not fuse into God but preserves the soul’s identity.

Then the longing for a more secluded life drew Ruusbroec from Brussels to the hermitage of Groenendaal – “green valley” – in the neighbouring Sonian Forest. Disciples soon joined him, and the hermitage became the motherhouse of a new congregation bearing its name. Frank van Coudenberg was appointed its first provost, with Ruusbroec as prior.

After Ruusbroec’s death in 1381, his relics were carefully kept and his memory honoured as that of a saint. His thought formed a bridge between the Friends of God and the Brethren of the Mean Life, ideas that may have prepared the way for the Reformation. In 1908 he was beatified by Pope Pius X.

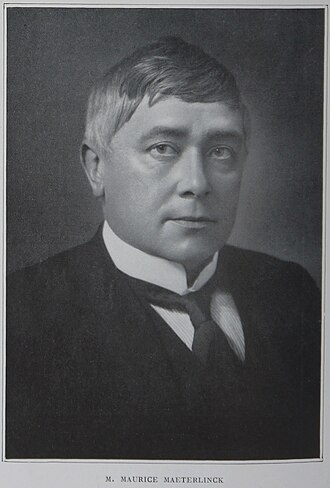

The Belgian writer and Nobel laureate Maurice Maeterlinck translated The Spiritual Espousals (Die gheestelike brulocht) into French in 1910. In his preface he wrote:

“I know few writers who are more clumsy than he; he sometimes lapses into strange childishness, and the first twenty chapters of his book, although they may form a necessary introduction, contain little more than dull platitudes. He repeats himself several times and sometimes seems to contradict himself. He combines the ignorance of a child with the knowledge of someone who has returned from the dead. Everywhere there is a monstrous disproportion between knowledge and ignorance, between strength and desire. Many will therefore see in his book little more than the work of a visionary monk, a gloomy recluse, a hermit, drunk with fasting and consumed by fever.

“And yet – this poor, lonely monk, who knew no Greek and perhaps no Latin, catches, in the midst of the dark Sonian Forest, in his ignorant, simple soul, the dazzling reflection of the highest and most mysterious peaks of human knowledge. Unconsciously, he knows the Platonism of Greece, the Sufism of Persia, the Brahmanism of India and the Buddhism of Tibet, and his marvellous ignorance rediscovers the wisdom of buried centuries and provides science with knowledge of centuries yet to come.”

The search for union with God – or Allah, or Existence itself – is universal. The seekers of the Low Lands sought God in their own ways: through a simple life of devotion, like the Brethren of the Mean Life; through the pursuit of scholarship, like Erasmus; or through contemplation in nature, like Ruusbroec. What they shared was longing – the same longing voiced by the Persian poet Rumi, who died not long before Ruusbroec was born:

Listen to the moan of a dog for its master.

That whining is the connection.

There are love dogs no one knows the names of.

Give your life to be one of them.

— Rumi (tr. Coleman Barks)

Comments are closed.