Sarita’s Sacred Tour in Ladakh continues from Leh to Uleytokpo, from where they visit the Alchi Monastery and the village Tar in a hidden valley (Part 2)

Journeying to Uleytokpo

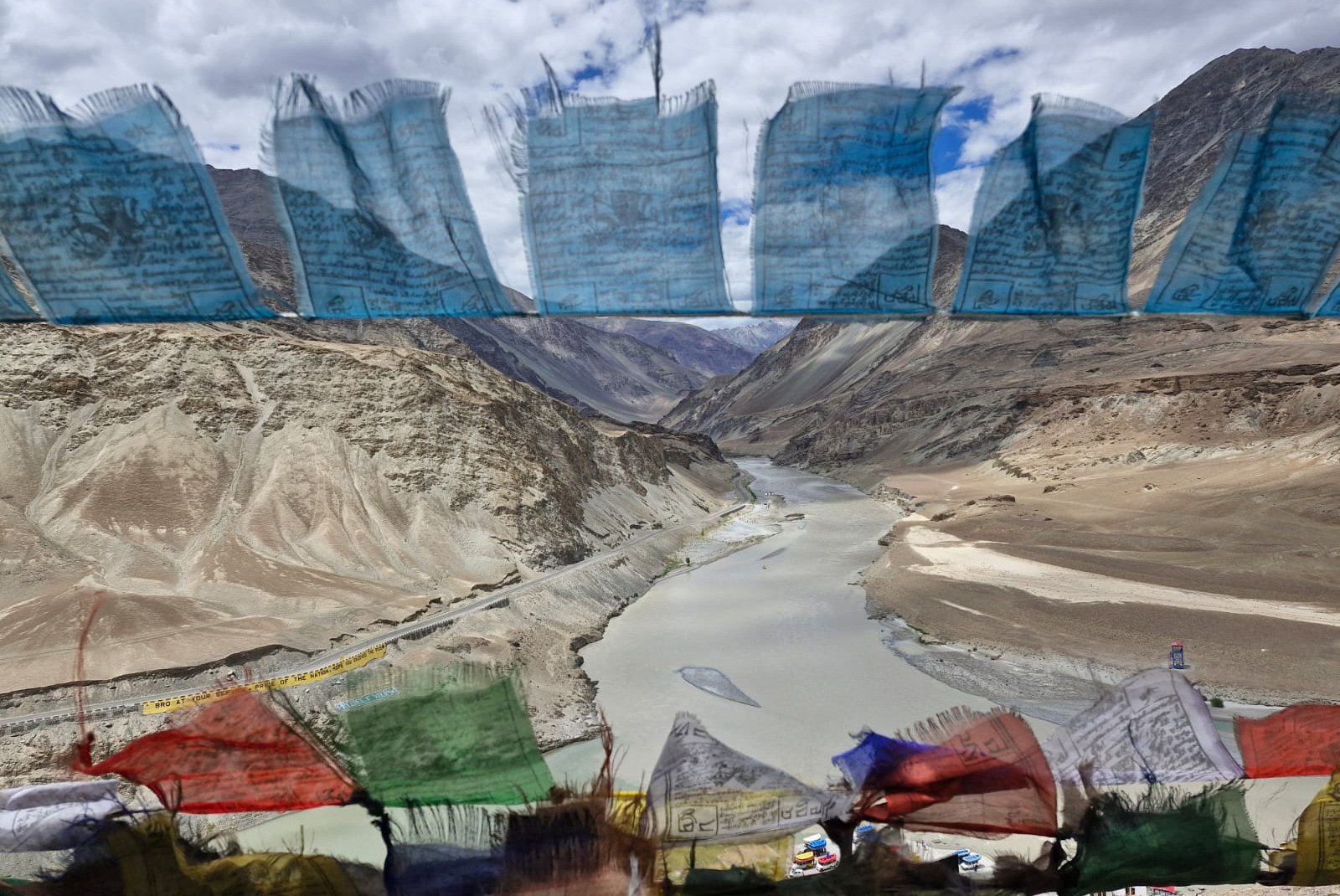

· Sangam – the meeting of Indus and Zanskar rivers

and visiting

· Alchi Monastery

Monday, 14 July 2025

Today, after breakfast, our caravan of cars, luggage strapped high on the roofs, set out through Ladakh’s dramatic terrain. The road seemed like the thinnest ribbon etched into the mountainsides, dwarfed on every side by the vast, jagged Himalayan peaks. Every turn revealed new vistas: barren cliffs striped with mineral hues, sweeping valleys shaped by ancient glaciers, and sky so intensely blue it almost looked painted.

The Confluence of Rivers – Sangam

We stopped at the famed confluence of the Indus and Zanskar Rivers, known locally as The Sangam. From the viewing point we watched the two rivers merge in a spectacular display of contrasts, the Indus with its shimmering green currents, flowing calmly from Tibet, and the Zanskar with its muddier, darker waters rushing from the Zanskar Valley. This natural phenomenon, located near the village of Nimmu, is considered one of Ladakh’s most awe-inspiring sights.

In summer, the Zanskar swells with glacial melt, feeding into the Indus with wild force. In winter, the Zanskar freezes solid, becoming the legendary Chadar Trek, where adventurers walk for days on sheets of ice through narrow gorges. It’s along the Indus banks that one of the world’s earliest civilisations, the Indus Valley Civilization (3300–1300 BCE), had flourished.

Our guide, Rahi, reminded us of the river’s deep cultural importance. Known as Sindhu in Sanskrit, the Indus gave India both its name and its civilisational identity. Ancient Persians referred to the people living beyond the Sindhu as Hindus, while the Greeks, influenced by Persian pronunciation, called the river Indos. Over centuries, Hindu became a cultural term, and under the British Raj, “India” was cemented as the country’s name. Within India itself, however, the traditional name has always been Bharat, as referenced in the country’s ancient texts like the Mahabharata and Puranas.

Arrival at Ule Ethnic Resort

Following the Indus upstream, our cars finally rolled into Ule Ethnic Resort, perching on a rocky hill overlooking the river. The place felt like a hidden oasis, almost too beautiful to be real. The resort’s eco-conscious ethos is evident everywhere: cottages built in harmony with the land, solar-powered lighting, and abundant gardens where apple, apricot, and walnut trees grow in profusion. Ladakh is famous for its apricots, introduced by Silk Road traders centuries ago, and during harvest season, locals dry them in the sun, turning them into one of the region’s most beloved staples.

Our group instantly fell in love with the resort’s rustic elegance. The cottages, more like luxurious glamping pods, are scattered among orchards where the sweet smell of ripening fruit perfumed the air. Climbing the steps to the dining hall, we were greeted with a vibrant vegan lunch, steaming lentil dishes, fresh greens from the garden, handmade breads, and inventive desserts infused with local apricots. After hours on the road, the meal was a feast for both body and spirit.

Osho’s No-Mind Meditation

In the afternoon, we gathered for Osho’s No-Mind Meditation in preparation for our next spiritual destination, Alchi Monastery. Osho’s meditation method emphasises releasing the constant stream of inner chatter. Through cathartic movement and gibberish speech, followed by silence, participants drop into a profound space of stillness. Practising it against the backdrop of Ladakh’s wild beauty made it feel even more powerful, like emptying ourselves so we could meet Alchi’s sacred presence with clear hearts.

Alchi Monastery with Manjushri’s Temple, a living time capsule

We then set off to visit Alchi Monastery, one of Ladakh’s oldest and most unique monastic complexes. Built between 958 and 1055 CE by the translator Rinchen Zangpo, who is said to have built 108 monasteries across the Himalayas, Alchi is a treasure trove of early Tibetan Buddhist art. Unlike other monasteries perched on hills, Alchi is nestled in the valley, along a shady lane lined with poplar and willow trees, giving it a gentle, almost hidden atmosphere.

Stepping inside felt like entering a time capsule. The low wooden doorways forced even the shortest among us to bow, a physical gesture of humility before the sacred. Inside, the walls are covered in murals, some of the oldest surviving in Ladakh. Painted in a distinct Kashmiri style, these frescoes depict Buddhas, bodhisattvas, mandalas, and intricate patterns that blend Indian, Tibetan, and Central Asian influences. Scholars often point out that Alchi preserves an artistic style largely lost in Tibet itself, making it invaluable for understanding the evolution of Buddhist art.

Though many of the murals are fading with age, their detail is breathtaking: serene faces outlined with delicate gold, intricate lotus motifs, and cosmological diagrams illustrating Buddhist philosophy. Massive clay statues dominate the temples, some reaching two stories high, their expressions a mixture of serenity and majesty.

We were particularly drawn to the small Manjushri Temple, built around a sacred cave. Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom, is depicted here with multiple heads and arms, each symbolising different aspects of awakened insight. Despite the tiny space, our entire group managed to squeeze in and sit together in meditation. For nearly an hour, we remained in silence, enveloped by the presence of centuries of prayer and by the etheric aura of Manjushri himself.

Osho has spoken on Manjushri. His quotes offer a powerful indication about the nature of this rare being.

“Manjushri was rare because he had the greatest quality of being a Master. Whenever somebody was too much of a difficult problem, somebody was a problematic person, Buddha would send him to Manjushri. Just the name of Manjushri and people would start trembling. He was really a hard man, he was really drastic. Whenever somebody was sent to Manjushri, the disciples would say, ‘That person has gone to Manjushri’s sword.’ It has become famous down the ages – the ‘sword of Manjushri’ – because Manjusri used to cut the head in one stroke. He was not a slow-goer, he would simply cut the head in one stroke. His compassion was so great that he could be so cruel. So by and by the name of Manjushri became a representative name – a name for all Masters, because they are all compassionate and they all have to be cruel. Compassionate because they will give birth to a new man in you; cruel because they will have to destroy and demolish the old.”

Alchi is also significant because it was not continuously maintained by monks like other monasteries. Instead, it was preserved largely by the local lay community, who considered it too sacred to abandon but too fragile to populate with daily rituals. This unusual circumstance may be why its ancient murals and statues survived Mongol invasions and natural erosion better than elsewhere.

Excursion with trek from Uleytokpo to

· Tar Village

Tuesday, 15 July 2025

After a delightful breakfast at our Ule Resort, we left at 9am for the traditional eco-village of Tar, nestled in the folds of the Himalayas. Tar can only be reached on foot, making it one of the most secluded inhabited valleys in Ladakh. Our cars carried us as far as possible on a long and precarious dirt road, before grinding to a halt at the end of the track. From there, the path narrowed into a trail winding upward into the mountains. It was here that our guide, Urgyan, a villager from Tar, appeared from behind a massive boulder, smiling warmly. Astonishingly, he was wearing nothing but a pair of simple house slippers, an almost humorous reminder of how lightly the people of these mountains tread upon terrain that feels challenging to outsiders.

Trek into a hidden valley

The ascent began with a sensory immersion into Ladakh’s living wilderness. A narrow river rushed down between enormous boulders, its waters crashing into cascades and tumbling into whirlpools, before settling into serene natural pools that sparkled like turquoise mirrors under the Himalayan sun. The sound of rushing water felt like the valley’s song – its own timeless mantra. Urgyan explained that though the pools look inviting, the water comes directly from glacial melt high above, and is icy enough to numb the body within moments.

At one point, our guide stopped and gestured to a spring bubbling directly from beneath a large rock. He encouraged us to drink, explaining that it was considered medicinal. Glacial spring water, untouched and mineral-rich, is prized in Ladakhi culture for its purity and vitality. The villagers believe such springs are blessings of the local deities, and drinking from them is both a physical and spiritual act. As I took a sip, I felt a rush of effervescent energy ripple through my body, a reminder of how alive water can feel when it has not been tamed or processed.

At one point, our guide stopped and gestured to a spring bubbling directly from beneath a large rock. He encouraged us to drink, explaining that it was considered medicinal. Glacial spring water, untouched and mineral-rich, is prized in Ladakhi culture for its purity and vitality. The villagers believe such springs are blessings of the local deities, and drinking from them is both a physical and spiritual act. As I took a sip, I felt a rush of effervescent energy ripple through my body, a reminder of how alive water can feel when it has not been tamed or processed.

Further along, Urgyan showed us a remarkable rock formation resembling the face of a wise lama. To the villagers, this natural feature is a sacred sign, a reminder to live in accordance with spiritual wisdom. Such features are often seen across the Himalayas, where nature itself is read as scripture and landscapes are imbued with teaching. The lama’s face, eternally gazing over the valley, seemed like a guardian.

Shrine to Goddess Dolma

Our path took us to a small shrine built into a cave, dedicated to Goddess Dolma, another name for Tara, the female bodhisattva of compassion. Tara is one of the most beloved figures in Tibetan Buddhism, seen as the “Mother of Liberation” who rescues beings from physical and spiritual suffering. Ladakhi villagers often invoke Dolma before beginning journeys, planting, or new ventures. The shrine, simple and adorned with prayer flags and butter-lamps, radiated a palpable sense of protection. We paused to offer prayers, knowing we were stepping deeper into a valley held by her guardianship.

Ancient petroglyphs

Not far beyond, we encountered petroglyphs of ibex carved into a rock face, their lines weathered but still visible. Urgyan explained that they are at least 10,000 years old, remnants of Ladakh’s prehistoric hunter-gatherer inhabitants. Archaeologists note that Ladakh has one of the world’s richest collections of petroglyphs. The ibex, still revered in Ladakh, is a symbol of agility and survival in these harsh terrains.

Arrival in Tar village

At last, the valley opened and we entered Tar Village itself. The effect was breathtaking. Green meadows spread across the valley floor, hemmed in by towering cliffs. The river wound its way gently past orchards and fields. Willow, poplar, and apricot trees gave shade, while the sound of water and birdsong created an atmosphere of total serenity. The village looked like a living Shangri-La, a place outside time, protected by its remoteness.

Sitting in the grass beside the river, Urgyan shared the story of Tar’s origins. About 500 years ago, two brothers who were pastoral nomads settled here. They raised sheep and goats, weaved their wool into clothing and blankets and traded them in nearby valleys. The village grew to about 80 residents at its peak. But as the modern world pressed into Ladakh, people began leaving, seeking education, jobs, and conveniences elsewhere. By the early 2000s, Tar was nearly abandoned.

What saved it was the vision of its youth. A group of young villagers who had left realised that their greatest treasure was not the outside world but their ancestral home. They returned, formed a youth collective and reimagined Tar as a model of sustainable living. They revitalised agriculture, restored old homes, and developed eco-tourism with homestays built from mud bricks, straw and stone, blending tradition with ecological innovation. Their efforts were so successful that Tar was recognised nationally as the Best Eco-Tourism Village in India.

Urgyan also told us about the village’s name. In Ladakhi, Tar means ‘ice sheet’. Centuries ago, a boy asked his father if he could cross the frozen river in winter to visit his uncle. The ice became the defining feature of the valley’s identity. To this day, locals remember that story whenever the river freezes over in the long winters.

A glimpse into village life

We toured organic gardens where barley, potatoes, and vegetables grew alongside medicinal herbs. Apricot trees hung heavy with fruit, Ladakh’s ‘golden crop’ used to make oils, jams, and dried snacks. We peeked inside one of the eco-homestays with the walls plastered with clay, the rooms warmed by traditional wood stoves, and every item handmade, from rugs woven on backstrap looms to lamps crafted by hand.

Not everything was idyllic. We were shown the traditional dry compost toilets, which consist of a hole layered with earth to decompose waste. Though ingenious in preserving scarce water resources, the small enclosed spaces smelled quite unpleasantly compared to the fresh mountain air outside…

A day of bliss

By midday, our group had dispersed into their own rhythms. Some sat in meditation by the river, others wandered the meadows, while a few napped in the sunshine, lulled by the sounds of water and wind. For lunch, the resort staff had prepared a lavish picnic feast, carried up the mountain path in neat containers. There was brown rice, fragrant vegetable pulao, curried tofu and vegetables, richly spiced potatoes, warming dal soup, and fresh salads. Eating such abundance in this remote paradise felt almost miraculous.

As I sat there, looking at the timeless beauty of Tar, I couldn’t help imagining the possibility of settling here, building a life rooted in the rhythms of land, river, and sky. The thought lingered: perhaps this is the kind of place where humanity might find its way back to balance, with the blessings of Goddess Dolma guiding the path.

I have to admit, my imagination ran riot, visualising the possibility of simply moving to Tar village and helping to establish a thriving eco-community there. Let’s see what the Goddess Dolma has in store…

To be continued…

Photographs by Rahi, Danelle and participants. Photo of Alchi Monastery (where photography is not allowed) credit to imvoyager.com

Source of discourse

- Osho, The Tantra Vision, Vol 1, Ch 1

Comments are closed.