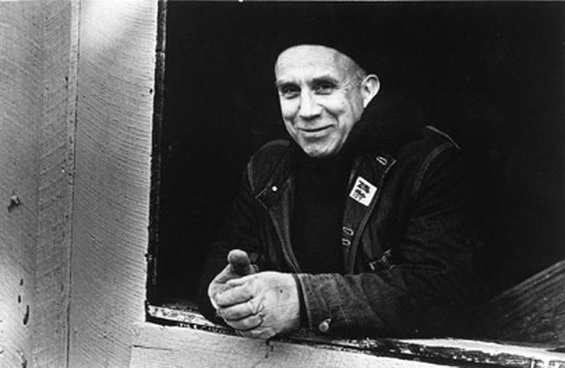

Thomas Merton (January 31, 1915 – December 10, 1968) was born in Prades, France.

After a rambunctious youth and adolescence, Merton converted to Roman Catholicism whilst at Columbia University in the USA, and in 1941 he entered the Abbey of Gethsemani, a community of monks belonging to the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (Trappists), the most ascetic Roman Catholic monastic order. The twenty-seven years he spent in Gethsemani brought about profound changes in his self-understanding.

Merton was a poet, social activist, and student of comparative religion. He wrote more than 70 books, mostly on spirituality, social justice and a quiet pacifism, as well as scores of essays and reviews on topics ranging from monastic spirituality to civil rights, nonviolence, and the nuclear arms race. Among his most enduring works is his bestselling autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain (1948), which sent scores of World War II veterans, students, and even teenagers flocking to monasteries across the USA.

Merton was a keen proponent of interfaith understanding. He pioneered dialogue with the Dalai Lama, D.T. Suzuki, and Thich Nhat Hanh, and authored books on Zen Buddhism and Taoism. For his social activism Merton endured severe criticism, from Catholics and non-Catholics alike, who assailed his political writings as unbecoming of a monk.

During his last years, he became deeply interested in Asian religions, particularly Zen Buddhism, and in promoting East-West dialogue. After several meetings with Merton during the American monk’s trip to the Far East in 1968, the Dalai Lama praised him as having a more profound understanding of Buddhism than any other Christian he had known.

The exact circumstances of his death in Bangkok are unclear.

Q: In Thomas Merton’s view: “Zen is not a systematic explanation of life, it is not an ideology, it is not a world view, it is not a theology of revelation and salvation, it is not a mystique, it is not a way of ascetic perfection, it is not mysticism as it is understood in the west; in fact it fits no convenient category of ours. Hence all our attempts to tag it and dispose of it with labels like pantheism, quietism, illuminism, pelagianism, must be completely incongruous.

“But the chief characteristic of Zen is that it rejects all systematic elaborations in order to get back as far as possible to the pure, unarticulated and unexplained ground of direct experience. The direct experience of what? Life itself.”

Beloved master,

Has Thomas Merton got it?

It is a very sad story about Thomas Merton. Perhaps he was one of the persons in the West who has come closest to Zen. He had the sensibility of a poet; the others are approaching Zen from their intellect, their mind.

Thomas Merton is approaching Zen through his heart. He feels it, but he could not live the direct experience he is talking about. He would have been the first Zen master in the West, but he was prevented by the Catholic Church.

Thomas Merton was a Trappist monk under the control of the Vatican. The Trappist monks are the most self-torturing ascetics in Christianity. Perhaps that’s why they are called Trappist – trapped forever.

There is every reason to suspect

that he was poisoned to prevent him

from going to a Zen monastery.

Thomas Merton wrote beautiful poetry, and he asked again and again to go to Japan and to live in a Zen monastery to have the direct experience of Zen. But permission was refused half a dozen times; again and again he was refused.

If he had really understood Zen he would not have bothered even to ask for permission. Who is the Vatican? Who is the pope? A Zen master asking permission from unenlightened people is simply not heard of. And he followed the orders from the Vatican and from the abbot of his own monastery.

He had been reading as much as was available in English about Zen. Finally, he had a chance to go, but he did not understand the way the organized religions work. There was going to be a Catholic conference of missionaries in Bangkok, Thailand, and he asked permission to attend the conference. Deep in his heart he was going to Bangkok to attend the conference just so that from there he could enter Japan without asking anybody’s permission.

But the pope and the Vatican leaders and his abbot – they were all aware of his continuously asking for permission to go to a Zen monastery.

On the last day of the conference in Bangkok, Thomas Merton spoke about Zen. And he also mentioned that he would love to go to Japan from Bangkok. That very night he was found dead. And without anybody being informed, his body was embalmed immediately, without any autopsy, without knowing the cause of his death. After you have embalmed a body there is no possibility of autopsy. There is every reason to suspect that he was poisoned to prevent him from going to a Zen monastery.

Murder has been the argument of the so-called religions. This is not a religious attitude at all. If he wanted to experience Zen, any religious man would have allowed him to go. That’s what happens in Zen. No master ever rejects any disciple’s interest in some other Zen monk, in some other monastery – maybe belonging to a different branch, Soto or Rinzai… Permission is gracefully given, and not only to those who are inquiring about going somewhere else. Even the master himself, if he feels that some other master will be more appropriate, some other path leading to the direct experience will be more fitting to the disciple, will send his own disciples to other monasteries. This is a totally different world, the world of Zen, with no competitiveness, no question of conversion.

Thomas Merton’s murder shows the poverty of Catholicism and Christianity. Why were they so afraid? The fear was that Thomas Merton had already praised Zen, and although he was living in the monastery, it seemed he was wavering between Zen and Christianity. To give him a chance to go to Japan and have a direct experience under a master might have been dangerous. He might have become involved in Zen for his whole life. These so-called religions are so jealous; they don’t have any compassion for individual growth, freedom.

Thomas Merton’s murder is not only Thomas Merton’s murder, it should make every Christian aware that Christianity is not a religion. Deep down it is more interested in gathering numbers. Numbers have their own politics. The greater the number of followers you have, the greater the power to dominate. And they are always afraid that anybody who leaves their fold is betraying.

But it is absolutely certain that Thomas Merton had already felt in his heart the immense need for Zen. Christianity was no longer satisfying. His whole life he had been a monk in the monastery, but slowly slowly, as he became aware of Zen, he could see that Christianity was not at all a religion; fictions, lies, beliefs, but not a direct experience. The very idea of Zen as a non-systematic, individualist approach to truth in a direct way – not through theology, not through any belief, not through any philosophy, but through meditation – was attracting him immensely, but it was not yet an experience.

Thomas Merton is far better than Suzuki, than Alan Watts, than Paul Reps, than Hubert Benoit, and than many others who have written about Zen. He comes the closest, because he is not speaking through the head, he is speaking through the heart of a poet.

But the heart is only just in the middle, between the head and the being. Unless you reach to the being, you don’t have the experience yourself. But he was a sensitive man; he managed to state things which he had not experienced.

The heart can understand

something deeper than the mind,

but Zen is far deeper than the heart.

The heart can be

just an overnight stay.

His statement is beautiful, but it shows clearly that he had not experienced it himself. This is his understanding – of course, far deeper than any other Western scholar of Zen. If it had really been a direct experience for him, the way he was saying, he would not have cared about anybody’s permission, he would not have cared about Christianity. He would have come out of that fold – which was just a slavery and nothing else.

Because he never came out of the fold, that shows he was hanging in the middle, he was not yet certain. He had not tasted the truth. He had only heard about it, read about it, and felt that there seems to be a different approach, altogether different, from that of Christianity. But Christianity was still keeping its hold over him. He could not be a rebel, and that’s where he failed, completely failed.

A man of Zen is basically rebellious. Thomas Merton was not rebellious, he was a very obedient person. Obedience is another name for slavery, a beautiful name that does not hurt you, but it is spiritual slavery. His asking six times and being refused, and still remaining in the fold, shows clearly that he was spiritually a slave. Although he was showing a deep interest in Zen, it was at the most, deeper than the mind, but not deep enough to reach to the being. He remained hanging in the middle. Perhaps now in his new life, he may either be here, or in Japan – most probably he is here amongst you – because that was his last wish before he died.

As the conference ended and he went to his bed, immediately he was poisoned. While he was dying, thinking about Zen, his last wish must have been to go to Japan, to be with a master. He had lived under Christianity his whole life, but it had not fulfilled him, it had not made him enlightened. It had only been a consolation.

Only fools can be deceived by consolations and lies and fictions. A man of such intense sensitivity as Thomas Merton could not be befooled. But a lifelong obedience turned into a spiritual slavery. He tried to sneak out from Bangkok – because there was no need to ask the abbot of the monastery, there was no need to ask the pope. He could have simply gone from Bangkok.

His desire to go to Japan shows

that he had seen one thing clearly:

that Christianity does not work.

But these so-called religions are murderous. They must have been ready. If he showed any interest in Japan and not going back to his monastery directly from Bangkok as the conference ended… the murderers must have been already there. And because he mentioned in his last speech to the conference that he was immensely interested in Zen, and he would like to go to Japan from there, this statement became his death.

[…] Thomas Merton was living in a Trappist monastery. Obviously, he could see that Zen does not give you any discipline, it is not ascetic, and he could see what he had been doing to himself and what other Trappists were doing to themselves. It is sheer masochism – self-torture in the name of an ascetic way of life. It is not a way of life, it is a way of death! It is slow suicide, slow poisoning.

But his statement will be detected by any man who has a direct experience of Zen. He says, “It is not a way of ascetic perfection.” The implication is that it is a way of perfection without asceticism. It is not a way of perfection at all.

Zen is evolution, endless evolution. Perfection is the dead end of the road, there is no more to go. In Zen there is always the infinite and the eternal available. You cannot exhaust it. In fact, as you go on the way, the way is not exhausted, slowly slowly you start dispersing and disappearing. Suddenly you find one day you are no more, only existence is.

It is not perfection at all, it is not salvation. It is dissolution, it is disappearance, it is melting like ice into the ocean.

Thomas Merton goes on, “It is not mysticism as it is understood in the West.”

In the West it is understood as mysticism; that does not mean it is not mysticism. Certainly it is not the mysticism that arises out of the mind as a philosophical point of view. It is pure mysticism, not originating in the mind, but arising from your very sources of life. It blossoms into mysterious flowers releasing mysterious, absolutely unknown fragrances into existence. It is mysticism – but it is not an “ism.” It is not a philosophy, it is not a creed or cult. Again and again you have to fall back towards direct experience.

He says, “In fact, it fits no convenient category of ours.”

All his statements are beautiful, but something is missing. That missing link you will find only if you have the experience. Then you can compare. Otherwise Thomas Merton will look absolutely right, a man of Zen. He is not. He wanted to be, but if he had been, there would have been no need to go to Japan. I have never been to Japan.

In fact, in Japanese Zen monasteries my books are being read, prescribed in Zen universities – but I have never been to Japan. I don’t need to. Buddha himself never went to Japan, Mahakashyapa was not born in Japan.

His desire to go to Japan shows that he had seen one thing clearly: that Christianity does not work. And he was searching for some new approach that worked. His statement, “In fact it fits no convenient category of ours,” is true. But it is not only categories of ours – it does not fit into any kind of category. It is beyond categories. Neither Christian categories, nor Hindu, nor Mohammedan, nor Jaina, it does not fit into any category. It is so original, you cannot make it fit into any category. The original is always individual; it is not a category.

Do you think I fit in any category? All categories are against me! And the reason they are against me is that I don’t fit with them. I have no desire to fit with anybody. I am sufficient unto myself. I don’t need any religion, I don’t need any philosophy, I don’t need any category.

In other words: I am a category in myself.

Zen will not fit into any category because it is a category in itself. And it is such a rebellious category, such an unsystematic category, that in Zen all kinds of wildflowers are accepted as equal with the roses and with the lotuses. It does not matter whether it is a lotus or a rose or just a wildflower, the only thing that matters is flowering. All have flowered to their potential. That’s where they are all equal. Otherwise their colours are different, their beauties are different, their fragrances are different – a few may not have any fragrance at all.

So they don’t fit in one category, but as far as flowering is concerned, they have all flowered, blossomed, to their totality. Whatever was hidden has become a reality. What was a dream in the plant has blossomed as a reality.

Zen is a blossoming of your potential. And everybody has a different potential, so when you blossom as a Zen man you have a unique individuality. You don’t fit with any category – and not only Christian categories. That’s what Thomas Merton means: “In fact, it fits no convenient category of ours.”

But I have to say to you, it does not fit any category at all, yours or ours or anybody else’s. It is beyond the mind. All categories belong to the mind. This is the only rebellion against mind: going beyond it. This is the only revolution against the self: going into no-self, into anatta. This is ultimate freedom from all kinds of bondages: prisons and categories and isms and ideologies and world views and philosophies. It is an absolute freedom from all that mind can create and mind can understand. It is also free from the heart.

The heart can understand something deeper than the mind, but Zen is far deeper than the heart. The heart can be just an overnight stay. While you are going towards your being, your heart, your art, your music, your dance, your poetry, your painting, your sculpture, can be just one night’s halt. But you have to go deeper. You have to reach to the very roots of your life, from where you are getting nourishment every moment, to the point where you are joined with existence, you are no longer separate.

“Hence all our attempts,” says Thomas Merton, “to tag it and dispose of it with labels like pantheism, quietism, illuminism, Pelagianism, must be completely incongruous.”

This is a very simple understanding which need not have any direct experience. And he comes to the point. He says, “But the chief characteristic of Zen is that it rejects all systematic elaborations in order to get back as far as possible to the pure, unarticulated and unexplained ground of direct experience. The direct experience of what? Life itself.”

A beautiful statement, but empty – a plastic flower with no fragrance and with no life in it. Otherwise, why did he want to go to Japan? If he had had this direct experience he is talking about, there was no need to go to Japan, and there was no need to remain in a Trappist monastery. He should have been a man of freedom.

But he could never attain that freedom. He was longing for it, he was desiring it – and you desire only because you don’t have it. If you have it, you don’t desire it.

And you have asked, “Beloved Master, has Thomas Merton got it?”

Not yet – but perhaps in this life. After being murdered by the Christians…

Osho, The Zen Manifesto: Freedom From Oneself, Ch 2, Q 1 (excerpt)

Comments are closed.