Punya writes about Vimalkirti’s last hours on 10 January 1981 – from her book, On the Edge.

One afternoon rumour spread that Vimalkirti had collapsed during his morning karate class in Buddha Hall and had been taken to hospital. We knew him as a samurai, one of the guards in Lao Tzu House, and as the husband of Turiya – one of the leading therapists – and as the father of little Tanya. But for me he was my next door (or rather next window) neighbour, the trickster.

There was a funny ritual between Vimalkirti and us girls in our room. His head would suddenly appear in our open window, his long blond hair falling sideways from his shoulders while he craned his neck from his own window, and ask: “Do you have a spare beedie?” Startled by his sudden appearance, we would search in our bags to see if we had one of these little Indian cigarettes. He must have enjoyed startling us, because to smoke his beedie on the bench outside the ashram he would have had to walk past our door anyway.

After a few days we heard that he was not likely to come out of his coma and that Osho had gone to see him. Many of his closer friends went to the hospital to sit with him in silence.

For a few months now all workers were entitled to have one day off per week. Our bodies had become weak: it was easy to catch amoebas that then dwelled in our bellies eating away at the already poor nourishment of the vegetables grown in the depleted Indian soil. For years Deeksha had managed to make us work eight-hour shifts while the rest of the ashram worked six hours, and now the days off were a chance for her creativity to materialise further projects. My day off was on a Saturday. That Friday night she told me that the following day at 7am I was meant to meet Prakash at the main gate and go with him to Vimalkirti’s hospital. It happened to be my 7th sannyas birthday and I could think of no better way to celebrate it than seeing Vimalkirti. I was glad to be able to repay, even just a little, what I had received from my friends when I had been sick.

Prakash climbed behind the steering wheel of his white shopping van and, sitting next to him, enjoying the ride, I wondered what our special mission was all about, as we were not carrying any food with us. Vimalkirti’s hospital room was a free-standing bungalow separate from the main building. When I became accustomed to the darkness inside, I hesitated to believe what I saw: his beautiful blond hair had been shaved off, also his beard, where now stubble had grown back. Winding tubes were attached to his body, connecting to different machines, to glass bottles and plastic pockets. In a grey blue rhythm a machine pumped air into his lungs and with a sharp click reversed the valves and expelled his breath with a sibilant noise. I was astonished to see headphones over his ears. I guessed he was listening to an Osho discourse. Even if his mind were no longer functioning in such a way as to understand the words, he would have no doubt sensed the loving melody of our master’s voice.

That morning in discourse, answering Garimo’s question: “Is there anything you can say about what is happening to Vimalkirti?” Osho said:

Nothing is happening to Vimalkirti – exactly nothing, because nothing is nirvana. […] ‘Nothing’ sounds like emptiness – it is not so. […] Break the word ‘nothing’ in two, make it to ‘no-thingness’, and then suddenly its meaning changes, the gestalt changes. Nothing is the goal of sannyas. One has to come to a space where nothing is happening; all happening has disappeared. The doing is gone, the doer is gone, the desire is gone, the goal is gone. One simply is – not even a ripple in the lake of consciousness, no sound. […]

I was so deeply touched when I heard his words a week later on the video:

Vimalkirti is blessed. He was one of those few chosen sannyasins who never wavered for a single moment, whose trust has been total the whole time he was here. He never asked a question, he never wrote a letter, he never brought any problem. His trust was such that he became, by and by, absolutely merged with me. He has one of the rarest hearts; that quality of the heart has disappeared from the world. He is really a prince, really royal, really aristocratic! Aristocracy has nothing to do with birth, it has something to do with the quality of the heart. […]

We suddenly became aware that he was a prince. We might have known it in the back of our minds but had even forgotten that he was German. He was as much part of the commune as anyone else, with no special privileges.

The day he had the haemorrhage I was a little worried about him, hence I told my doctor sannyasins to help him remain in the body at least for seven days. He was doing so beautifully and so fine, and then just to end suddenly when the work was incomplete… He was just on the edge – a little push and he would become part of the beyond. […]

Seeing us standing there helplessly and empty handed, Puja, the nurse, asked us to clean the room. We looked around and wondered where we should begin: it was definitely an Indian hospital. We opted to go for the floor. In the adjoining storage room we found heavy-duty scrubbing brushes, a can of Vim and a metal bucket for water. On my knees I attacked with determination the years of dirt in the cracks between the terracotta tiles. Looking up at the narrow bed with Vimalkirti’s thin body I said in silent words: “You see, Kirti, I am just a kitchen worker. What else can I do for you than clean this floor?”

All of a sudden Puja shouted in distress: “The pressure is dropping, the pressure is dropping!” and waved us to immediately clear our gear and leave the room. We both sat on the bench outside, leaning against the wall of the main building. We had no idea what was happening: puzzling scraping metal noises came from the room, as if heavy furniture was being moved about. A gust of warm wind blew across our faces, swaying us from side to side. Its delicate whooshing sound erased all thoughts in my mind and the world bleached in front of my eyes like an over-exposed photograph. Steadying ourselves again we held on tight to the rim of the concrete bench. We looked at each other, speechless, trying to find out what this was all about. Prakash’s stare confirmed he was plunged in the same dizzy vacuum and revealed no further clue.

Amrito walked towards our bench with a folded piece of paper in his hand. His inexplicable smile did not help us in solving the mystery either. He asked if one of us wanted to deliver a note to Nirvano. I was unable to move and said I wanted to remain there. Puja called us back to help. While we walked down to Vimalkirti’s room we saw a girl jump into a rickshaw and drive off to the ashram with the letter in her hand.

Many questions have come to me about what I think of living through artificial methods. Now, he is breathing artificially. He would have died the same day – he almost did die. Without these artificial methods he would have already been in another body, he would have entered another womb. But then I will not be available here by the time he comes. Who knows whether he would be able to find a master or not? – and a crazy master like me! And once somebody has been so deeply connected with me, no other master will do. They will look so flat, so dull, so dead!

Hence I wanted him to hang around a little more. Last night he managed: he crossed the boundary from doing to non-doing. That ‘something’ that was still in him dropped. Now he is ready, now we can say goodbye to him, now we can celebrate, now we can give him a send-off. Give him an ecstatic bon voyage! Let him go with your dance, with your song!

When I went to see him, this is what transpired between me and him. I waited by his side with closed eyes – he was immensely happy. […] So last night when I told him, ‘Vimalkirti, now you can go into the beyond with all my blessings’, he almost shouted in joy, ‘Farrr out!’ I told him, ‘Not that long!’ And I told him a story…

The crow came up to the frog and said, ‘There is going to be a big party in heaven!’

The frog opened his big mouth and said, ‘Farrr out!’

The crow went on, ‘There will be great food and drinks!’

And the frog replied, ‘Farrr out!’

‘And there will be beautiful women, and the Rolling Stones will be playing!’

The frog opened his mouth even wider and cried, ‘Farrr out!’

Then the crow added, ‘But anyone who has a big mouth won’t be allowed in!’

The frog pursed his lips tightly together and mumbled, ‘Poor alligator! He will be disappointed!’ […]

This accident is an accident for the people who are on the outside, but for Vimalkirti himself it has proven a blessing in disguise. You cannot get identified with such a body: the kidneys not functioning, the breathing not functioning, the heart not functioning, the brain totally damaged. How can you get identified with such a body? Impossible. Just a little alertness and you will become separate – and that much alertness he had, that much he had grown. So he immediately became aware that ‘I am not the body, I am not the mind, I am not the heart either.’ And when you pass beyond these three, the fourth, turiya, is attained, and that is your real nature. Once it is attained it is never lost. […]

There was silence in Vimalkirti’s room. The breathing machine had been stopped. The struggle to keep life going was over. His body, now wrapped in a red cloth, had come to rest. A few people had arrived from the ashram and had brought a bamboo stretcher. They asked me to help lift his body onto it from the bed. The body was light and I could feel its warmth through the soft velvet cloth. His chest, I saw, was no longer breathing. Anando spread drops of Osho’s camphor lotion around Vimalkirti’s body. It was the beautiful scent Osho used in earlier years. Coming close to him in the darshans we could smell it. Once I got a whiff of it on the beach in Goa, with no one around.

Vimalkirti’s body was carried away. Prakash and I were left behind to help clean up the room. The nurse told us what to pack and what remained with the hospital. I was happy to have something practical to do. We loaded the van with boxes of gauzes and pieces of equipment. At our medical centre we dropped everything off as quickly as we could and rushed to the burning ghats.

These are the ‘three L’s’ of my ‘philousia’: life, love, laughter. Life is only a seed, love is a flower, laughter is fragrance. Just to be born is not enough, one has to learn the art of living; that is the A of meditation. Then one has to learn the art of loving; that is the B of meditation. And then one has to learn the art of laughing; that is the C of meditation. And meditation has only three letters: A, B, C.

So today you will have to give a beautiful send-off to Vimalkirti. Give it with great laughter. Of course, I know you will miss him – even I will miss him. He has become such a part of the commune, so deeply involved with everybody. I will miss him more than you because he was the guard in front of my door, and it was always a joy to come out of the room and see Vimalkirti standing there, always smiling. Now it will not be possible again. But he will be around here in your smiles, in your laughter. He will be here in the flowers, in the sun, in the wind, in the rain, because nothing is ever lost – nobody really dies, one becomes part of eternity.

So even though you will feel tears, let those tears be tears of joy – joy for what he has attained. Don’t think of yourself, that you will be missing him, think of him, that he is fulfilled. And this is how you will learn, because sooner or later many more sannyasins will be going on the journey to the farther shore and you will have to learn to give them beautiful send-offs. Sooner or later I will have to go, and this is how you will also learn to give me a send-off with laughter, dance and song.

My whole approach is of celebration. Religion to me is nothing but the whole spectrum of celebration, the whole rainbow, all the colours of celebration. Make it a great opportunity for yourself, because in celebrating his departure many of you can reach to greater heights, to new dimensions of being; it will be possible. These are the moments which should not be missed; these are the moments which should be used to their fullest capacity.

Osho, Zen: Zest Zip Zap and Zing, Ch. 15

At the burning ghats I found a space on top of the wall at the end of the slope. From there I had a clear view onto the wide river, the lit funeral pyre and the hundreds of sannyasins, in their fiery colours, who had gathered around it. Anubhava’s song Step into the holy fire, step into the holy flame, took on a tangible reality for all of us, Oh, hallelujah, Oh, hallelujah. Singing my heart out I addressed Vimalkirti’s beautiful memory. My torso swayed from side to side, covering my face with my heavy dark hair. At times lost in the feeling of love and bliss, at times aware of the astonishment and wonder in my mind, I felt the cells of my body vibrating finely, giving me the sensation of growing in size. Was Vimalkirti leaving his life energy behind for all of us to savour? Like a balloon I was carried in swirls and lifted off into space, as if he had wanted to take me with him wherever he was flying off to.

The feeling of expansion followed me for the next few days. I tried to hide it: maybe others would also see the light I felt burning inside me. Deeksha’s sharp eyes immediately detected it and I got a special job. Now aware of my artistic talent, she asked me to lay out the inscription for Vimalkirti’s samadhi. There was going to be a marble grave for his ashes in Lao Tzu garden. With quick pencil strokes and with the help of a wooden ruler the words given to me on a little piece of paper found their place, size 1:1, on a big sheet of architects’ paper. I was amazed to see that the line under ‘Swami Anand Vimalkirti’ should read – in brackets – ‘Prince Welf of Hanover, Germany’. Later I heard that he was a cousin to the Prince of Wales and that Osho had invited the Prince of Wales to come and visit the ashram. I think Vimalkirti met him in Mumbai. The ashram was probably too hot a spot for a future king.

There was not much creativity involved in the drawing as Deeksha already had her own idea how the inscription should be: the same as on Dadaji’s samadhi. Not until I was half way through the job did I become aware that I was involved in an ugly competition between Deeksha and Samudaya, the ashram calligrapher. He was a stern man who was working for the publications department. I later heard that he had survived Auschwitz. His layout was presented in beautifully rounded, old-fashioned letters, drawn to perfection in black ink. But still ours was chosen, to Deeksha’s delight and triumph. It made sense just because it was easier and more practical for the Indian stone carver.

My next special job was to dispose of a heap of aluminium pots which had been collected outside Deeksha’s office. Instead of taking the job fully into my hands – finding out by myself who would buy them from us – I asked her: “But where…?” and that was the end of my ‘special job’. I was put back into the ranks of all other kitchen workers. I so much wanted to have a demanding job, but somehow always managed to mess it up. On the one hand I was safe hiding in my little black hole but on the other hand regretted not having taken the challenge.

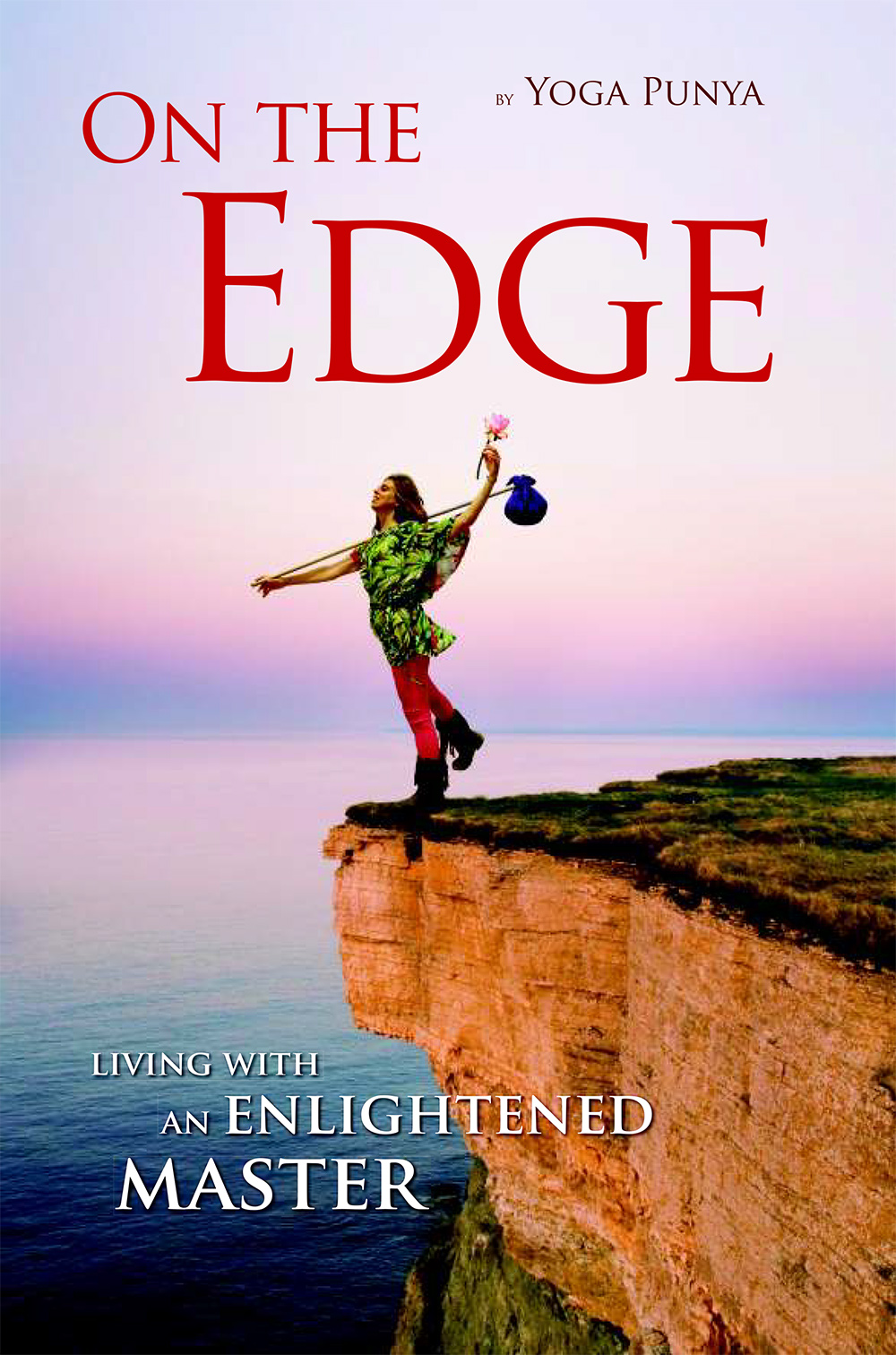

Excerpted from On the Edge by Yoga Punya

On the Edge

On the Edge

Living with an Enlightenend Master

by Yoga Punya

KDP Self-published, 10 Feb. 2015

ISBN-13: 978-1507787960

ASIN: B00THDXDM8

438 pages

Related articles

- Vimalkirti’s last evening darshan with our beloved Master – A true story from Aruna’s memories from the golden era of the Shree Rajneesh Ashram, aka Pune 1

- Each moment the last – Osho mentions Aruna’s letter about Vimalkirti’s death. “Be herenow, as if this is the last moment…”

- I saw you – Vimalkirti’s poem for his Master, Osho

- I wanted to know how to die – Iain McNay from Conscious TV interviews Turiya Hanover

- On the Edge – Madhuri reviews Punya’s book about living with Osho

Comments are closed.