“It’s perhaps the boldest statement ever made by any human being in any age in any part of the world, and I don’t think it can be improved upon in the future, ever.”

Beloved Osho, The most fundamental upanishidic statement is aham brahmasmi. Is it connected in any way to sachchidanand?

Anando, the statement in the Upanishads, aham brahmasmi, is perhaps the most fundamental and the most essential experience of all the mystics of the world. The Upanishads are the only books which are considered not to belong to any religion, yet they are the very essence of religiousness.

This statement, aham brahmasmi, is a declaration of enlightenment – literally it means, “I am the divine, I am the ultimate, I am the absolute.” It is a declaration that, “There is no other God than my own inner being.” This does not mean that it is a declaration of a single individual about himself. It is a declaration, of course, by one individual, but it declares the potential of every individual.

It denies God as a separate entity. It denies God as a creator. It denies God as a ruler. It simply denies the existence of God, other than in our own existence. It is the whole search of the Eastern genius. In thousands of years, they have discovered only one thing: don’t look for God outside your own being. If you can find him you can find him only in one place and that is in you – other than you all the temples and all the mosques and all the synagogues and all the churches are inventions of the priests to exploit you. They are not in the service of God; on the contrary they are exploiting all the potential gods.

Aham brahmasmi is perhaps the boldest statement ever made by any human being in any age in any part of the world, and I don’t think it can be improved upon in the future, ever. Its courage is so absolute and perfect that you cannot refine it, you cannot polish it. It is so fundamental that you cannot go deeper than this, neither can you go higher than this.

This simple statement aham brahmasmi… in Sanskrit is only three words. In English also it can be translated in these few words: “I am the Ultimate.” Beyond me there is nothing; there is no height that is not within me and there is no depth which is not within me. If I can explore myself I have explored the whole mystery of existence.

But, unfortunately, even the people of this country – where this statement was made some five thousand years ago – have forgotten all about the dignity of human beings. This statement is nothing but the ultimate manifesto of man and his dignity. Even in this country, where such individuals existed who reached the ultimate awakening and illumination, there are people who are worshipping stones. There are people who are enslaved by ignorant priests. There are people who are living in the bondage of a certain religion, creed or cult. They have forgotten the golden age of the Upanishads.

Perhaps that was the most innocent time that happened in the history of man. At that time the West was almost barbarous, and that barbarousness somehow has remained as an undercurrent in the Western consciousness. Otherwise, it cannot be just coincidental that the two great world wars have happened in the West. And preparation for the third is also happening in the West – just within a small span of half a century.

The days of the Upanishads in this land were the most glorious. The only search, the only seeking, the only longing, was to know oneself – no other ambition ruled mankind. Riches, success, power, everything was absolutely mundane.

Those who were ambitious, those who were running after riches, those who wanted to be powerful were considered to be psychologically sick. And those who were really healthy psychologically, spiritually healthy, their only search was to know oneself and to be oneself and to declare to the whole universe the innermost secret. That secret is contained in this statement, “Aham brahmasmi.” The people who followed the days of the Upanishads in a way have fallen into a dark age.

You will be surprised to know that the idea of involution has not appeared at all in the Western mind, only the idea of evolution, only the idea of progress. But the mystics of the Upanishads have a more perfect and more comprehensive approach. Nothing can go on evolving forever. Evolution has been conceived by the Upanishads as a circle and, in fact, in existence everything moves in a circle. Stars move in circles, the sun moves in a circle, the earth moves in a circle, the moon moves in a circle, climates move in a circle, life moves in a circle.

The whole existence knows only one way of movement and that is circular. So that which seems to be going up one day will soon be going down. Again, it will come up – it is just like a wheel and the spokes of the wheel. The same spoke will come up, will go down, will come up, will go down.

Evolution is incomplete if there is not any complementary idea of involution. Materially man has evolved. Certainly, there were no railway trains and there were no atomic weapons and there was no nuclear war material, there was no electricity, there was nothing of the technology that we have become accustomed to living with. Materially, man has certainly evolved, but spiritually, the situation is totally different.

Spiritually, man has not evolved. According to the Upanishads, man has gone deeper into darkness. He has lost his innocence and he has lost his blissfulness and he has lost his simple experience of: “I am the mysterious, I am the miraculous; I am the whole cosmos in a miniature form, just as a dewdrop is the whole ocean in a miniature form.” The dewdrop can declare, “I am the ocean,” and there will not be anything wrong in it. Certainly, a particular individual is only a dewdrop, but he can declare, “Aham brahmasmi,” and there is nothing wrong in it. He is simply saying the truth.

The Upanishads talk about four stages of man’s fall, not of evolution. The first stage, when the Upanishads came into being, is called the “Age of Truth.” People were simply truthful, just as small children are simply truthful.

To lie, one needs some experience. Lying is a complicated phenomenon, truth is not. To lie you need a developed memory, you have to remember what kind of thing you have said to one person and what kind of thing you have said to another person. A lying person needs a good memory. A man of truth needs no memory because he is simply saying that which is the case.

The child has no experience other than the truth, other than what he experiences. He cannot lie. The days of the Upanishads are the days of man’s childhood, of purity and innocence, of deep love and trust. The first age the Upanishads call Satyuga, the Age of Truth. Truth was not a long journey. You were not to go anywhere to find it. You were living in it.

The situation was exactly expressed by Kabir in a symbolic parable: A fish in the ocean, who must have had a philosophic bent, started inquiring of other fish, “I have heard so much about the ocean, but I want to know where it is.”

The poor fish that she questioned had also heard about the ocean but they were not so curious, so they never bothered about where it was. They said, “We have also heard about the ocean, but where it is we have never bothered to ask, and we don’t know the answer.”

And the young philosopher fish went on asking everybody, “Where is the ocean?” And they were all stunned. They had heard about it from their forefathers – it had always been known – but as far as an exact description or experience was concerned, nobody was able to explain it to the young fish.

Finally, the young fish declared, “You are all stupid. There is no ocean at all.” Nobody could answer the fish.

Kabir says the same is the situation of man. Man goes on asking, “Have you seen God? Have you seen the mysterious, the miraculous?” And all he can hear is, “We have heard about it, we have read about it . . .” But there was a day when people were so innocent, childlike, that they knew it – that they are surrounded by the ocean, that the ocean is not to be searched for, it is within and without. They are part of it, they are born in it, they live in it, they breathe in it, and they will one day disappear into it. They are part and parcel of the ocean.

But every child has to grow. And just as every child has to grow, Satyuga, the Age of Truth, could not remain forever. It produced the great scriptures called the Upanishads – the word is so beautiful: it simply means ‘sitting by the side of the master’ – those are recordings from the notes of disciples who were sitting in silence by the side of the master. Once in a while, out of his meditation, he would say something; out of his heart something would be transferred to the disciple, and the disciple would take a note. Those notes are the Upanishads.

Satyuga, the Age of Truth, disappeared – the child grew. The second stage is called Treta – it is compared to a table. The first, Satyuga, the Age of Truth, was almost like a table with four legs, absolutely balanced. Treta means three. One leg of the table has disappeared. Now it is no more a table with four legs, with that certainty, with that trust, with that grounding, with that centering, with that great balance . . . Now it is only a tripod, three legs.

Certainly, something is missing. It is not so certain – some doubt has arisen, trust is no longer complete and perfect, love is no more unpolluted. The disciple’s question is not coming from his whole being, just out of his head. But still, there was much yet to happen. The child went on growing. As far as age is concerned it seems a growth, but as far as innocence is concerned it is an involution. Both are going side by side: evolution as far as age and body are concerned, and involution as far as innocence, trust and love are concerned.

After Treta humanity fell still more. The stage after Treta is called Dwapar. One leg is lost again – now everything is unbalanced. Standing on two legs, how can a table have trust, certainty, security, safety, balance? Fear became the predominant quality rather than love, rather than trust. Insecurity became more prominent than a tremendous feeling of being at home. But things went on growing in one direction: as far as material growth is concerned, there was evolution; in another direction as far as consciousness is concerned, there was a continuous fall.

After Dwapar, the age of two legs, is the age we are living in. It is called Kaliyuga, the Age of Darkness. Even the last leg has disappeared. Man is almost in a state of insanity. Instead of innocence, insanity has become our normal state. Everybody is in some way or other psychologically sick.

I am talking about these four ages for a particular reason, because the statement that was made in innocence in the days of the Upanishads has become absolutely incomprehensible to our people, to our contemporaries. Even the people who are the inheritors of the Upanishads are afraid to declare that, “I am God,” that, “I am the Absolute” – what to say about others? Others have their own prejudices.

For example, when Christians started translating the Upanishads they were shocked. They could not believe that there are in existence scriptures so tremendously poetic, beautiful, but what they are saying goes against Christianity, against Judaism, against Mohammedanism, even against today’s Hinduism. Even the Hindu is not capable today of declaring, “I am God.” He has also become impressed and influenced by Christianity to such an extent.

Christian missionaries started condemning the Upanishads because if the Upanishads are right, then what to do with the Bible? The Bible absolutely declares, just as the Koran declares, that there is only one God. If the Upanishads are right then there are as many gods as there are living beings. Some may have come to manifestation, some may be on the way, some may not have started the journey yet but will start finally.

How long can you delay? You can miss one train, you can miss another train, but every moment the train is coming. How long can you go on sitting in the waiting room? And people go on becoming buddhas, and people go on becoming seers and sages, and you are still waiting in the waiting room with your suitcases. How long can you do that? There is a limit when you see that so many people have left already – the whole platform is empty – you will take courage that perhaps it is time to move.

For Christianity the problem was that everybody cannot be God. They cannot even accept everybody to be the son of God, what to say about God? Only Jesus is the son of God.

You are only puppets made of earth. God made man with mud and breathed life into it. It is just a manufactured thing, and if a puppet starts declaring, “Aham brahmasmi” – “I am God” – the puppeteer will laugh, saying, “Idiots! You are just puppets and your strings are in my hands. When I want you to dance you dance, when I want you to lie down you lie down, when I want you to breathe you breathe, when I want you not to breathe you can’t do anything.”

For Christianity it was a tremendous challenge, and they started finding arguments against it. Their first argument was that the person, the seer, the sage – whoever he may be, because even the name is not mentioned in the Upanishads – who declared for the first time, “Aham brahmasmi,” the Christian missionaries started saying that he was a megalomaniac, that he was suffering from a big ego. They were full of prejudice. They could not see the simple fact that it was not the ego that was declaring – because the Upanishads say it clearly: unless your ego disappears, you cannot even understand the meaning of “I am the Ultimate.”

It is not the declaration of ego. This declaration is possible only on the death of ego. That is a clear-cut statement in the Upanishads. But Christian missionaries went on misinterpreting the Upanishads to the West, distorting and commenting that these people were almost mad. Obviously, to a Mohammedan or to a Christian, the idea that somebody says, “I am God,” is very shocking. […]

When Christians – particularly the learned, scholarly missionaries – started translating the Upanishads, they distorted it in every way and they made comments, saying, “This is a statement of somebody who is utterly insane, whose ego is too big. And he is not religious at all, because a religious man should be humble. How can a religious man declare, ‘I am God’?”

This is very strange about religions. They can see the faults of each other but they cannot see their own faults. When Jesus declares, “I am the only begotten son of God,” they don’t see any ego – it is humbleness.

The Upanishads are not egoistic. They are not saying that the one sage who declares, “I am God,” is saying something only about himself. He is saying that you are also God – just as I am God, you are God. We are all part of a godliness. We are all part of the same ocean. This fish and that fish are not different; they are all born out of the same ocean and they will all disappear into the same ocean.

The Upanishads’ statement is not egoistic at all, but religions which are God-centered cannot accept it easily. Even Hindus, whose forefathers made this statement, have become so cowardly that now they do not dare to make such a statement. They themselves think that it is egoistic.

Christianity and Mohammedanism have both impressed too much – even on the Hindu mind. The Hindu mind is no longer pure Hindu. […]

And you are asking, Anando, what is the connection between this great statement – it is actually called mahavakya: ‘the great statement’ – with another statement of the same significance, sachchidanand. Sachchidanand consists of three words, as I have told you: Sat – truth; Chit – consciousness; Anand – bliss. These three experiences make one capable of asserting the great statement, “Aham brahmasmi.” They are deeply connected. In fact, if sachchidanand is the flower, then “Aham brahmasmi” is the fragrance, so deep is the connection between the two.

Certainly, “I am the Ultimate” is the very conclusion of the whole search of the East – of all the Buddhas, of all the mystics. A single sentence can be called the conclusion of the whole of India. But God-centered religions will not be ready to accept it. That simply shows that their understanding is not of truth, not of consciousness, not of bliss.

Their understanding is of a very low order: it is not an experience, but only a belief. One is a Christian only by belief; a Jew only by belief; a Mohammedan only by belief. What the Upanishads are saying is not any belief – it is direct, immediate experience. And they are so poetic, so mystic, that there is no comparison in the whole world’s literature.

But this final flowering and fragrance is possible only if you start with meditation and not with prayer. These two ways will take you to different conclusions: prayer will take you more and more into fiction and meditation will take you more and more into truth. Meditation is to go withinwards, and prayer is to look upwards, into the empty sky, with all your desires and greed and demands, with all your fears and insecurities. God is to you, if you are on the path of prayer, a consolation and nothing more, but if you are on the path of meditation, God will become one day your very own self, your very own existence. […]

If you want fictions, prayer is the path. All the religions that are based on prayer are not authentic religions.

But meditation is a totally different route. It takes you inwards; it takes you away from the world towards your own being. It is not a demand, it is not a desire, it is not greed, it is not asking or requesting anything. It is simply being silent, utterly silent, moving deeper and deeper into silence . . .

And a moment comes of sublime silence, and then a sudden explosion of light and you will feel yourself saying, “Aham brahmasmi.” Not outwards, because you are not saying it to anybody in particular – it will be just a feeling in the deepest core of your being. No language is needed, just an experience that, “I am the whole, I am the all. And just as I am the whole, everybody else is,” so there is no question of any ego or megalomania.

The Christian missionaries who interpreted the Upanishads were absolutely prejudiced and had no understanding about meditation and no understanding about the higher qualities of a true religion. They knew only an organized church. In comparison to the Upanishads, every religion of the world looks so ‘pygmy’, so childish.

Those organized religions don’t give you freedom. On the contrary, they give you deeper and deeper bondage and slavery. In the name of God, you have to surrender, in the name of God you have to become a sheep and allow a Jesus or a Mohammed to be a shepherd. It is so disgusting, the very idea is so self-disrespectful that I cannot call it even pseudo-religious. It is simply irreligious.

The Upanishads are the highest flights of consciousness. They don’t belong to any religion. The people who made these great statements have not even mentioned their names. They don’t belong to any nation, they don’t belong to any religion, they don’t belong to those who are in search of some mundane thing.

They belong to the authentic seekers of truth.

They belong to you.

They belong to my people.

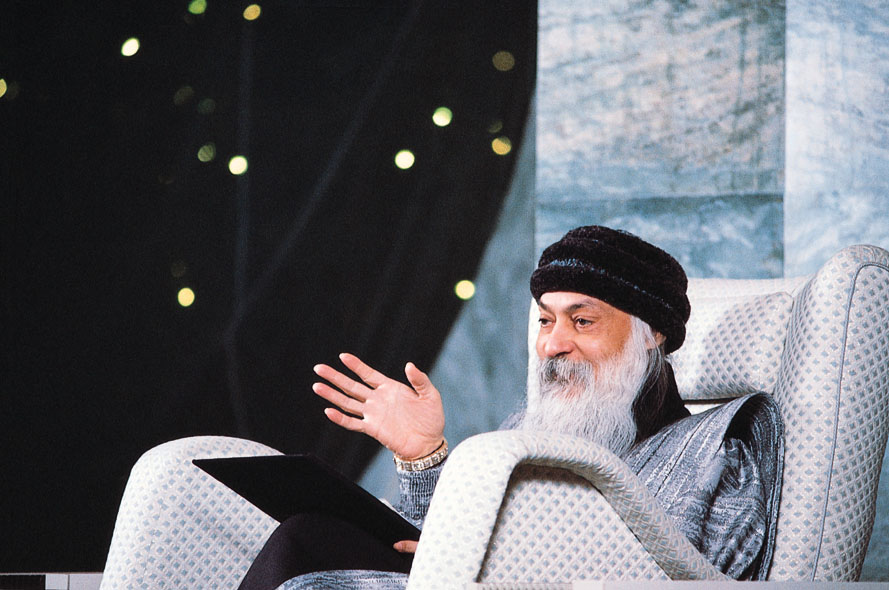

Osho, Sat Chit Anand: Truth, Consciousness, Bliss, Ch 12, Q 1

Credit to Sat Sanga Salon

Comments are closed.